While we try to keep things accurate, this content is part of an ongoing experiment and may not always be reliable.

Please double-check important details — we’re not responsible for how the information is used.

Education and Employment

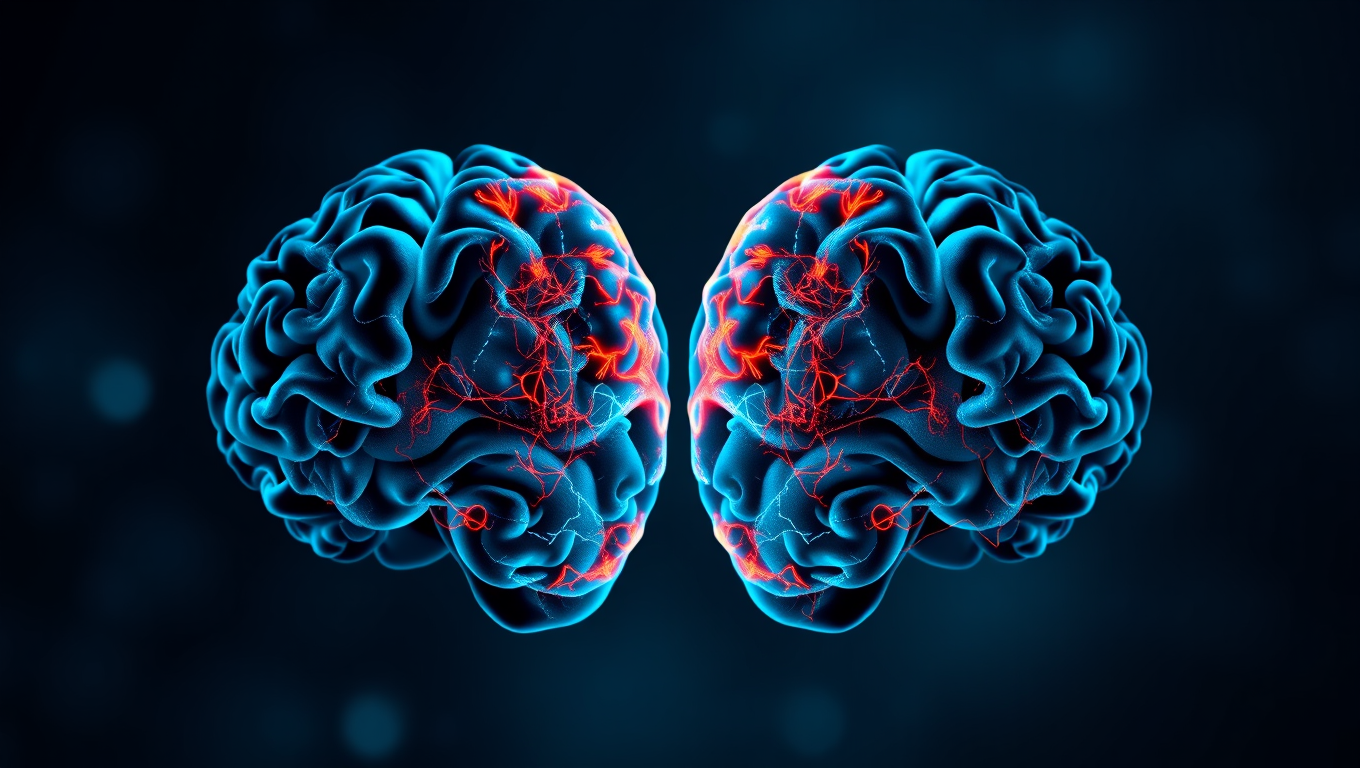

Optimists’ Brains Work Together, Pessimists’ Do Not: A Scientific Explanation

When imagining the future, optimists’ brains tend to look remarkably alike, while pessimists show more varied neural activity. This neurological alignment could explain why optimists are often more socially in sync with others.

Computer Graphics

The Quiet Threat to Trust: How Overreliance on AI Emails Can Harm Workplace Relationships

AI is now a routine part of workplace communication, with most professionals using tools like ChatGPT and Gemini. A study of over 1,000 professionals shows that while AI makes managers’ messages more polished, heavy reliance can damage trust. Employees tend to accept low-level AI help, such as grammar fixes, but become skeptical when supervisors use AI extensively, especially for personal or motivational messages. This “perception gap” can lead employees to question a manager’s sincerity, integrity, and leadership ability.

Cancer

Safer Non-Stick Coatings: Scientists Develop Alternative to Teflon

Scientists at the University of Toronto have developed a new non-stick material that rivals the performance of traditional PFAS-based coatings while using only minimal amounts of these controversial “forever chemicals.” Through an inventive process called “nanoscale fletching,” they modified silicone-based polymers to repel both water and oil effectively. This breakthrough could pave the way for safer cookware, fabrics, and other products without the environmental and health risks linked to long-chain PFAS.

Artificial Intelligence

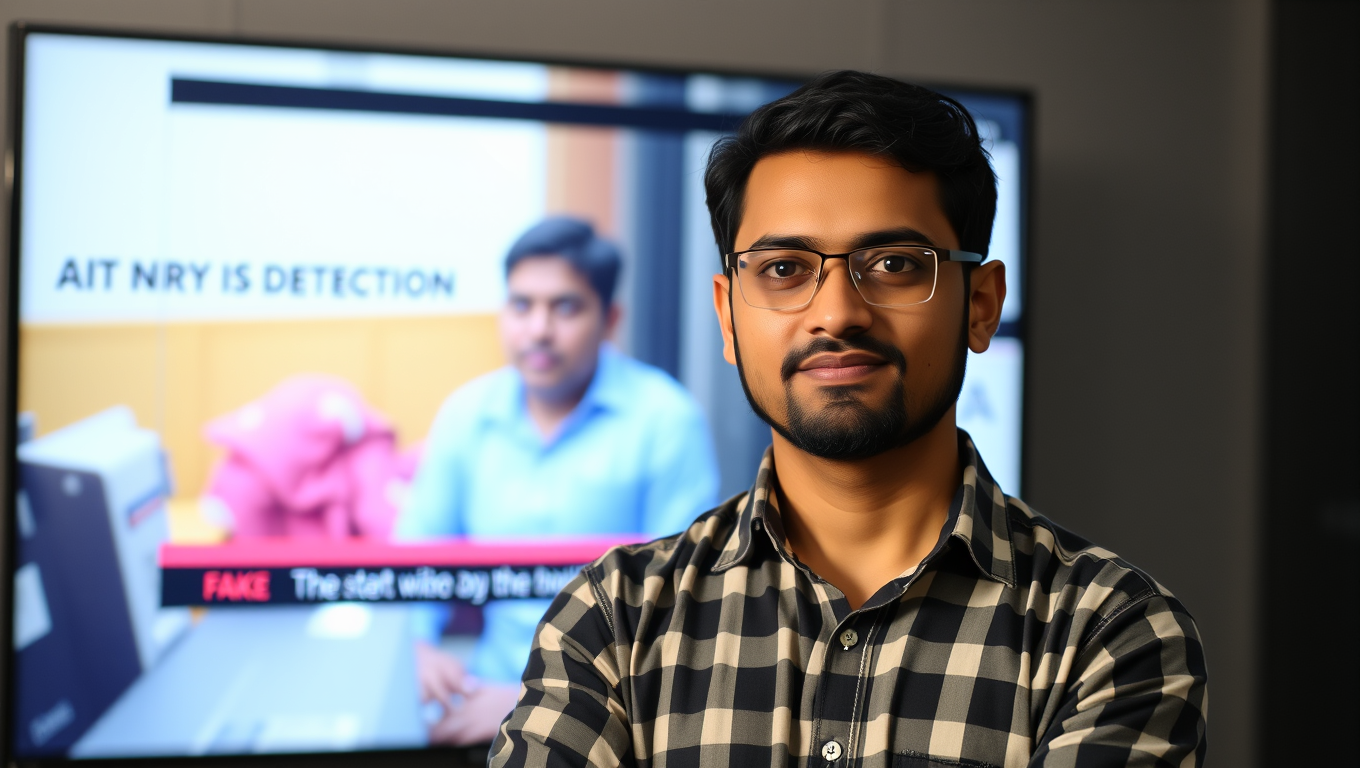

Google’s Deepfake Hunter: Exposing Manipulated Videos with a Universal Detector

AI-generated videos are becoming dangerously convincing and UC Riverside researchers have teamed up with Google to fight back. Their new system, UNITE, can detect deepfakes even when faces aren’t visible, going beyond traditional methods by scanning backgrounds, motion, and subtle cues. As fake content becomes easier to generate and harder to detect, this universal tool might become essential for newsrooms and social media platforms trying to safeguard the truth.

-

Detectors10 months ago

Detectors10 months agoA New Horizon for Vision: How Gold Nanoparticles May Restore People’s Sight

-

Earth & Climate11 months ago

Earth & Climate11 months agoRetiring Abroad Can Be Lonely Business

-

Cancer11 months ago

Cancer11 months agoRevolutionizing Quantum Communication: Direct Connections Between Multiple Processors

-

Albert Einstein11 months ago

Albert Einstein11 months agoHarnessing Water Waves: A Breakthrough in Controlling Floating Objects

-

Chemistry10 months ago

Chemistry10 months ago“Unveiling Hidden Patterns: A New Twist on Interference Phenomena”

-

Earth & Climate10 months ago

Earth & Climate10 months agoHousehold Electricity Three Times More Expensive Than Upcoming ‘Eco-Friendly’ Aviation E-Fuels, Study Reveals

-

Agriculture and Food11 months ago

Agriculture and Food11 months ago“A Sustainable Solution: Researchers Create Hybrid Cheese with 25% Pea Protein”

-

Diseases and Conditions11 months ago

Diseases and Conditions11 months agoReducing Falls Among Elderly Women with Polypharmacy through Exercise Intervention