While we try to keep things accurate, this content is part of an ongoing experiment and may not always be reliable.

Please double-check important details — we’re not responsible for how the information is used.

Atmosphere

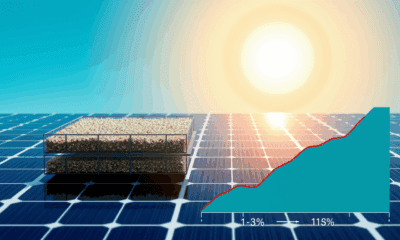

“Saharan Storms Cloud Europe’s Solar Future: The Dark Side of Dust”

New research reveals how Saharan dust impacts solar energy generation in Europe. Dust from North Africa reduces photovoltaic (PV) power output by scattering sunlight, absorbing irradiance, and promoting cloud formation. The study, based on field data from 46 dust events between 2019 and 2023, highlights the difficulty of predicting PV performance during these events. Conventional forecasting tools often fail, so the team suggests integrating real-time dust load data and aerosol-cloud coupling into models for better solar energy scheduling and preparedness.

Acid Rain

Uncovering the Hidden Trigger Behind Massive Floods

Atmospheric rivers, while vital for replenishing water on the U.S. West Coast, are also the leading cause of floods though storm size alone doesn t dictate their danger. A groundbreaking study analyzing over 43,000 storms across four decades found that pre-existing soil moisture is a critical factor, with flood peaks multiplying when the ground is already saturated.

Atmosphere

Biofilms Hold Key to Stopping Microplastic Build-up in Rivers and Oceans

Where do microplastics really go after entering the environment? MIT researchers discovered that sticky biofilms naturally produced by bacteria play a surprising role in preventing microplastics from accumulating in riverbeds. Instead of trapping the particles, these biofilms actually keep them loose and exposed, making them easier for flowing water to carry away. This insight could help target cleanup efforts more effectively and identify hidden pollution hotspots.

Atmosphere

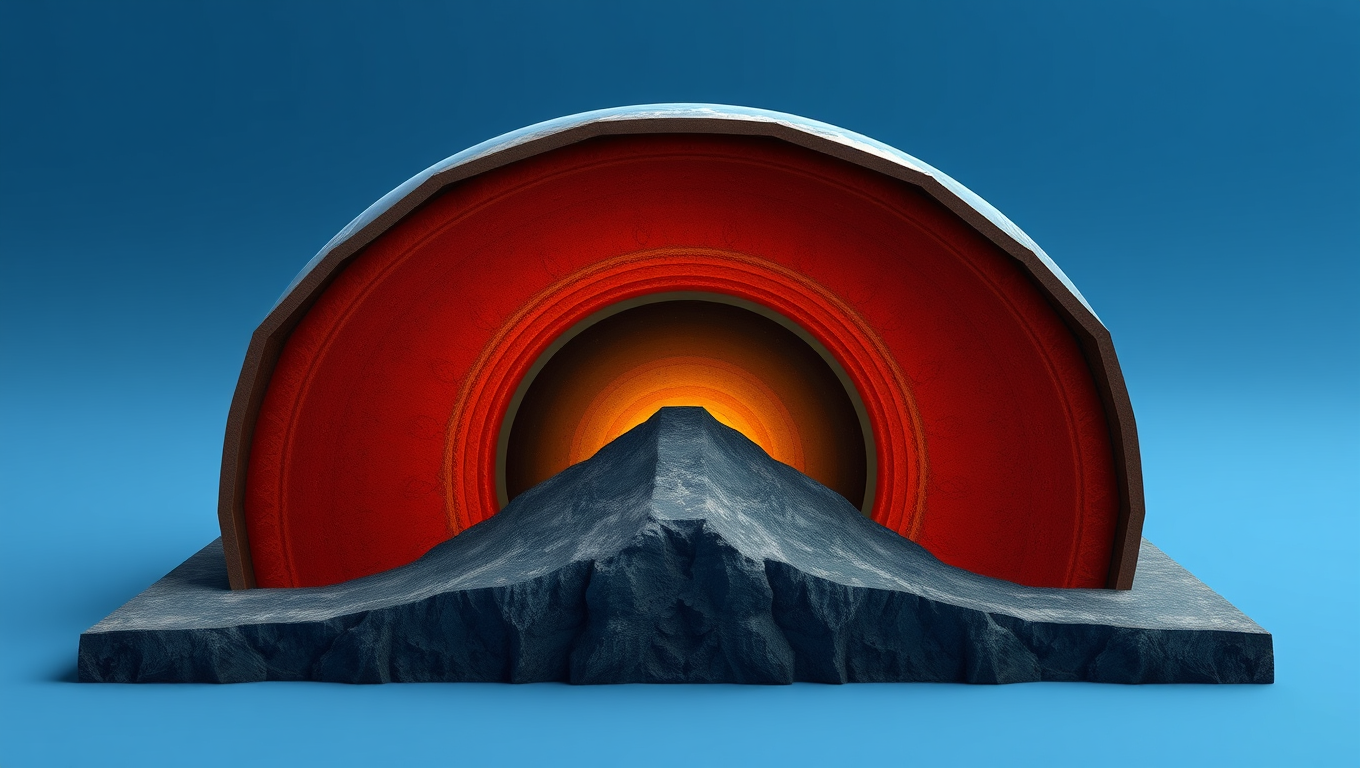

Unveiling the Secrets of Earth’s Core: How Solid Rock Flows 3,000 Kilometers Below Us

Beneath Earth s surface, nearly 3,000 kilometers down, lies a mysterious layer where seismic waves speed up inexplicably. For decades, scientists puzzled over this D” layer. Now, groundbreaking experiments by ETH Zurich have finally revealed that solid rock flows at extreme depths, acting like liquid in motion. This horizontal mantle flow aligns mineral crystals called post-perovskite in a single direction, explaining the seismic behavior. It s a stunning leap in understanding Earth s deep inner mechanics, transforming a long-standing mystery into a vivid map of subterranean currents that power volcanoes, earthquakes, and even the magnetic field.

-

Detectors2 months ago

Detectors2 months agoA New Horizon for Vision: How Gold Nanoparticles May Restore People’s Sight

-

Earth & Climate4 months ago

Earth & Climate4 months agoRetiring Abroad Can Be Lonely Business

-

Cancer3 months ago

Cancer3 months agoRevolutionizing Quantum Communication: Direct Connections Between Multiple Processors

-

Agriculture and Food3 months ago

Agriculture and Food3 months ago“A Sustainable Solution: Researchers Create Hybrid Cheese with 25% Pea Protein”

-

Diseases and Conditions4 months ago

Diseases and Conditions4 months agoReducing Falls Among Elderly Women with Polypharmacy through Exercise Intervention

-

Albert Einstein4 months ago

Albert Einstein4 months agoHarnessing Water Waves: A Breakthrough in Controlling Floating Objects

-

Earth & Climate3 months ago

Earth & Climate3 months agoHousehold Electricity Three Times More Expensive Than Upcoming ‘Eco-Friendly’ Aviation E-Fuels, Study Reveals

-

Chemistry3 months ago

Chemistry3 months ago“Unveiling Hidden Patterns: A New Twist on Interference Phenomena”