While we try to keep things accurate, this content is part of an ongoing experiment and may not always be reliable.

Please double-check important details — we’re not responsible for how the information is used.

Climate

Save Twice the Ice by Limiting Global Warming

A new study finds that if global warming exceeds the Paris Climate Agreement targets, the non-polar glacier mass will diminish significantly. However, if warming is limited to 1.5 degrees Celsius, at least 54 per cent could be preserved — more than twice as much ice as in a 2.7 C scenario.

Climate

The Ocean’s Fragile Fortresses: Uncovering the Impact of Climate Change on Bryozoans

Mediterranean bryozoans, including the “false coral,” are showing alarming changes in structure and microbiomes under acidification and warming. Field studies at volcanic CO₂ vents reveal that these stressors combined sharply reduce survival, posing risks to marine ecosystems.

Climate

Unraveling Chaotic Ant Wars to Save Coffee: The Complexities of Ecological Systems in Agriculture

In a Puerto Rican coffee farm, researchers uncovered a web of chaotic interactions between three ant species and a predator fly, revealing how shifting dominance patterns make pest management unpredictable. By combining theories of cyclic dominance and predator-mediated coexistence, they showed how ecological forces oscillate and intertwine, creating patterns too complex for simple forecasting. This deep dive into ant behavior underscores both the potential and the challenges of replacing pesticides with ecological methods, as nature’s own “rules” prove to be far from straightforward.

Climate

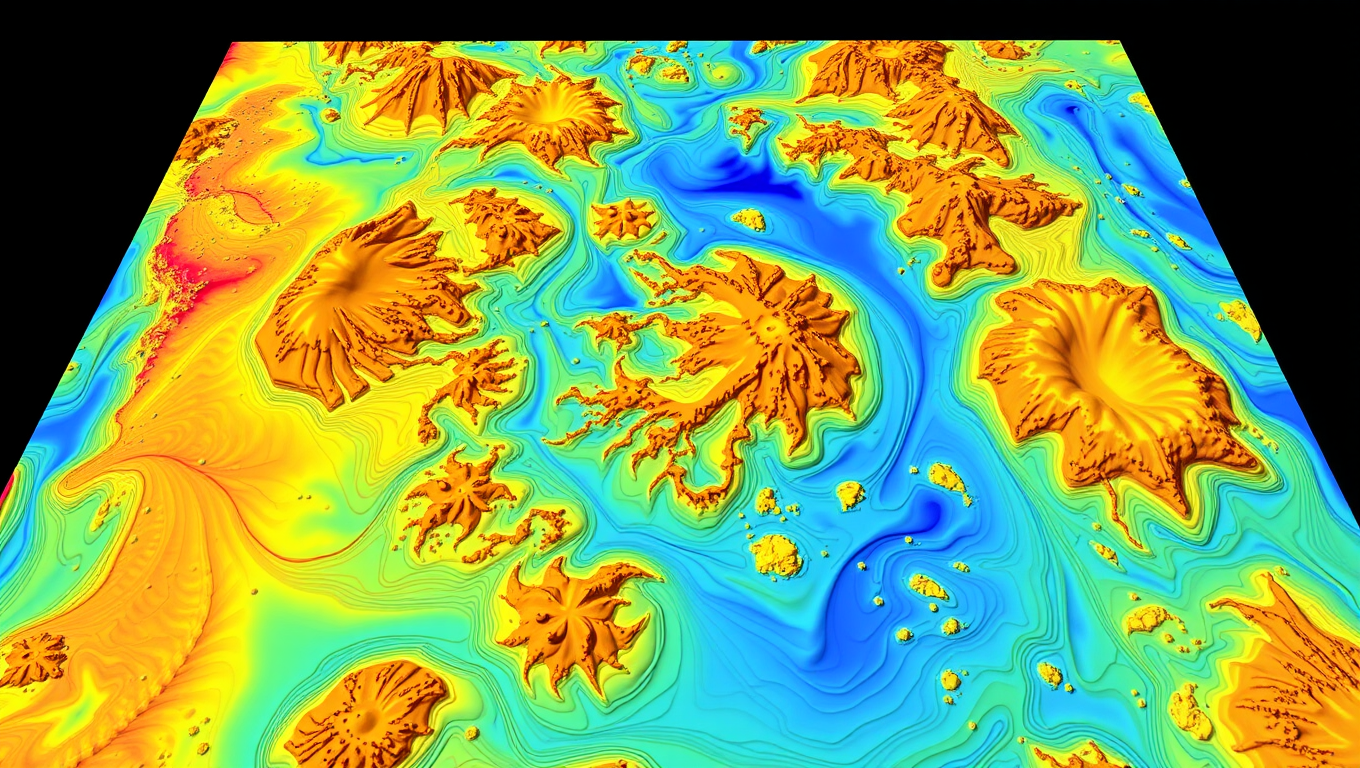

“Hidden Wonders: Scientists Stunned by Colossal Formations Under the North Sea”

Beneath the North Sea, scientists have uncovered colossal sand formations, dubbed “sinkites,” that have mysteriously sunk into lighter sediments, flipping the usual geological order. Formed millions of years ago by ancient earthquakes or pressure shifts, these giant structures could reshape how we locate oil, gas, and safe carbon storage sites. The discovery not only challenges established geology but also introduces a new partner phenomenon, “floatites,” and sparks debate among experts.

-

Detectors11 months ago

Detectors11 months agoA New Horizon for Vision: How Gold Nanoparticles May Restore People’s Sight

-

Earth & Climate12 months ago

Earth & Climate12 months agoRetiring Abroad Can Be Lonely Business

-

Cancer12 months ago

Cancer12 months agoRevolutionizing Quantum Communication: Direct Connections Between Multiple Processors

-

Albert Einstein12 months ago

Albert Einstein12 months agoHarnessing Water Waves: A Breakthrough in Controlling Floating Objects

-

Chemistry11 months ago

Chemistry11 months ago“Unveiling Hidden Patterns: A New Twist on Interference Phenomena”

-

Earth & Climate12 months ago

Earth & Climate12 months agoHousehold Electricity Three Times More Expensive Than Upcoming ‘Eco-Friendly’ Aviation E-Fuels, Study Reveals

-

Diseases and Conditions12 months ago

Diseases and Conditions12 months agoReducing Falls Among Elderly Women with Polypharmacy through Exercise Intervention

-

Agriculture and Food12 months ago

Agriculture and Food12 months ago“A Sustainable Solution: Researchers Create Hybrid Cheese with 25% Pea Protein”