While we try to keep things accurate, this content is part of an ongoing experiment and may not always be reliable.

Please double-check important details — we’re not responsible for how the information is used.

Climate

Unraveling the Secrets of Faults: How Wide Are They, Really?

Researchers posed a seemingly simple question: how wide are faults?

Atmosphere

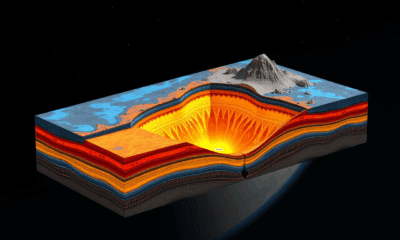

Uncovering the Hidden Link: NASA Discovers Connection Between Earth’s Core and Life-Sustaining Oxygen

For over half a billion years, Earth’s magnetic field has risen and fallen in sync with oxygen levels in the atmosphere, and scientists are finally uncovering why. A NASA-led study reveals a striking link between deep-Earth processes and life at the surface, suggesting that the planet’s churning molten interior could be subtly shaping the conditions for life. By comparing ancient magnetic records with atmospheric data, researchers found that these two seemingly unrelated phenomena have danced together since the Cambrian explosion, when complex life first bloomed. This tantalizing connection hints at a single, hidden mechanism — perhaps even continental drift — orchestrating both magnetic strength and the air we breathe.

Climate

A 123,000-Year-Old Warning: Coral Fossils Reveal Rapid Sea-Level Rise Ahead

Ancient coral fossils from the remote Seychelles islands have unveiled a dramatic warning for our future—sea levels can rise in sudden, sharp bursts even when global temperatures stay steady.

Air Quality

Flash Floods on the Rise: How Climate Change Supercharges Summer Storms in the Alps

Fierce, fast summer rainstorms are on the rise in the Alps, and a 2 C temperature increase could double their frequency. A new study from researchers at the University of Lausanne and the University of Padova used data from nearly 300 Alpine weather stations to model this unsettling future.

-

Detectors3 months ago

Detectors3 months agoA New Horizon for Vision: How Gold Nanoparticles May Restore People’s Sight

-

Earth & Climate4 months ago

Earth & Climate4 months agoRetiring Abroad Can Be Lonely Business

-

Cancer3 months ago

Cancer3 months agoRevolutionizing Quantum Communication: Direct Connections Between Multiple Processors

-

Agriculture and Food3 months ago

Agriculture and Food3 months ago“A Sustainable Solution: Researchers Create Hybrid Cheese with 25% Pea Protein”

-

Diseases and Conditions4 months ago

Diseases and Conditions4 months agoReducing Falls Among Elderly Women with Polypharmacy through Exercise Intervention

-

Albert Einstein4 months ago

Albert Einstein4 months agoHarnessing Water Waves: A Breakthrough in Controlling Floating Objects

-

Earth & Climate3 months ago

Earth & Climate3 months agoHousehold Electricity Three Times More Expensive Than Upcoming ‘Eco-Friendly’ Aviation E-Fuels, Study Reveals

-

Chemistry3 months ago

Chemistry3 months ago“Unveiling Hidden Patterns: A New Twist on Interference Phenomena”