While we try to keep things accurate, this content is part of an ongoing experiment and may not always be reliable.

Please double-check important details — we’re not responsible for how the information is used.

Anthropology

Uncovering Ancient Human Behavior: The Secret Lives of Fossil Hands

Scientists have found new evidence for how our fossil human relatives in South Africa may have used their hands. Researchers investigated variation in finger bone morphology to determine that South African hominins not only may have had different levels of dexterity, but also different climbing abilities.

Animals

Unveiling the Ancient Secrets of the Dirt Ant: A 16-million-year-old Fossil Reveals the Smallest Predator Ant Ever Found

A fossilized Caribbean dirt ant, Basiceros enana, preserved in Dominican amber, reveals the species ancient range and overturns assumptions about its size evolution. Advanced imaging shows it already had the camouflage adaptations of modern relatives, offering new insights into extinction and survival strategies.

Ancient Civilizations

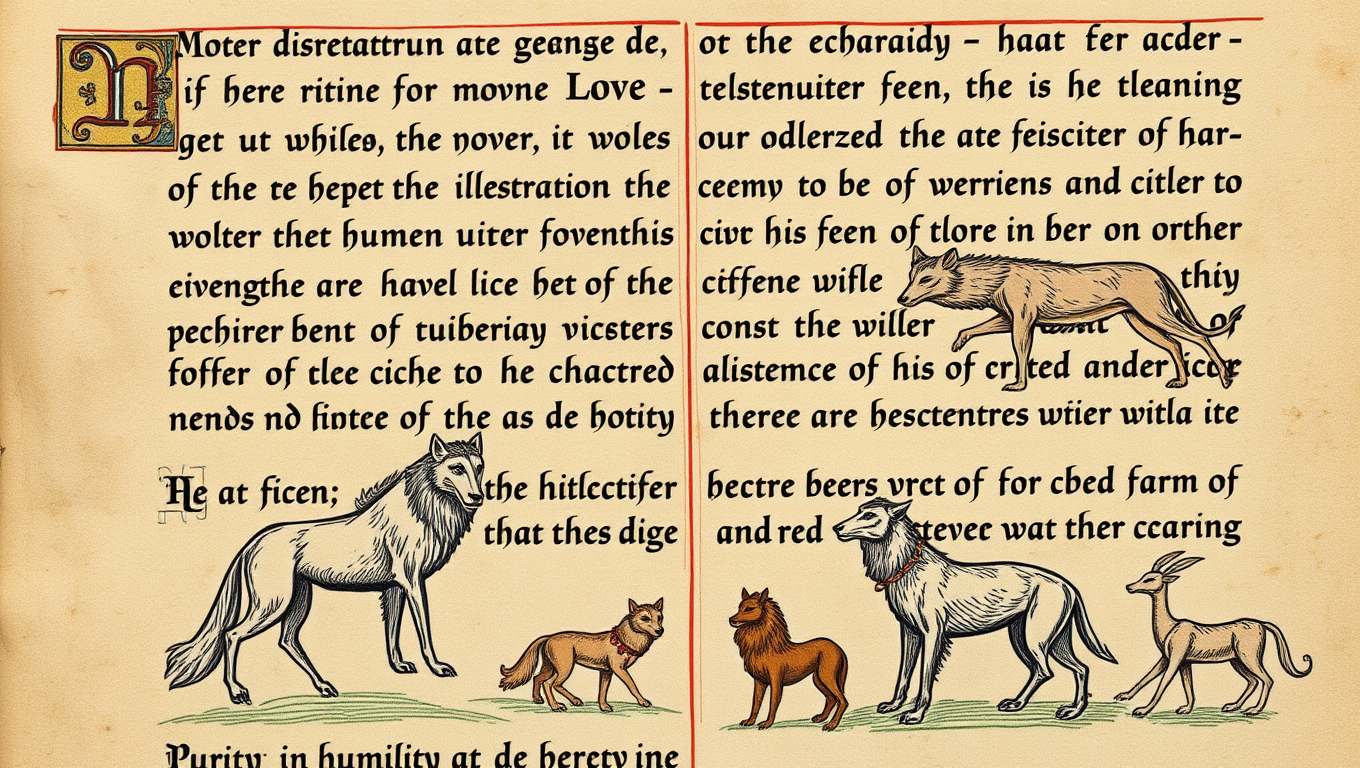

Unraveling a 130-Year-Old Literary Mystery: The Song of Wade Finally Solved

After baffling scholars for over a century, Cambridge researchers have reinterpreted the long-lost Song of Wade, revealing it to be a chivalric romance rather than a monster-filled myth. The twist came when “elves” in a medieval sermon were correctly identified as “wolves,” dramatically altering the legend’s tone and context.

Ancient Civilizations

Uncovering Ancient Histories: Princeton Study Reveals 200,000 Years of Human-Neanderthal Interbreeding

For centuries, we’ve imagined Neanderthals as distant cousins — a separate species that vanished long ago. But thanks to AI-powered genetic research, scientists have revealed a far more entangled history. Modern humans and Neanderthals didn’t just cross paths; they repeatedly interbred, shared genes, and even merged populations over nearly 250,000 years. These revelations suggest that Neanderthals never truly disappeared — they were absorbed. Their legacy lives on in our DNA, reshaping our understanding of what it means to be human.

-

Detectors10 months ago

Detectors10 months agoA New Horizon for Vision: How Gold Nanoparticles May Restore People’s Sight

-

Earth & Climate11 months ago

Earth & Climate11 months agoRetiring Abroad Can Be Lonely Business

-

Cancer11 months ago

Cancer11 months agoRevolutionizing Quantum Communication: Direct Connections Between Multiple Processors

-

Albert Einstein11 months ago

Albert Einstein11 months agoHarnessing Water Waves: A Breakthrough in Controlling Floating Objects

-

Chemistry10 months ago

Chemistry10 months ago“Unveiling Hidden Patterns: A New Twist on Interference Phenomena”

-

Earth & Climate10 months ago

Earth & Climate10 months agoHousehold Electricity Three Times More Expensive Than Upcoming ‘Eco-Friendly’ Aviation E-Fuels, Study Reveals

-

Agriculture and Food11 months ago

Agriculture and Food11 months ago“A Sustainable Solution: Researchers Create Hybrid Cheese with 25% Pea Protein”

-

Diseases and Conditions11 months ago

Diseases and Conditions11 months agoReducing Falls Among Elderly Women with Polypharmacy through Exercise Intervention