While we try to keep things accurate, this content is part of an ongoing experiment and may not always be reliable.

Please double-check important details — we’re not responsible for how the information is used.

Diabetes

Beyond Ozempic: A New Weight Loss Drug on the Horizon

Tufts University scientists are aiming to revolutionize the future of weight loss drugs by engineering a new compound that targets four gut hormones instead of the usual one to three. These next-gen tetra-functional peptides may overcome the limitations of current drugs like Ozempic and Mounjaro especially their nausea, muscle loss, and rebound weight gain.

Allergy

“The Silent Invader: How a Parasitic Worm Evades Detection and What it Can Teach Us About Pain Relief”

Scientists have discovered a parasite that can sneak into your skin without you feeling a thing. The worm, Schistosoma mansoni, has evolved a way to switch off the body’s pain and itch signals, letting it invade undetected. By blocking certain nerve pathways, it avoids triggering the immune system’s alarms. This stealth tactic not only helps the worm survive, but could inspire new kinds of pain treatments and even preventative creams to protect people from infection.

Colon Cancer

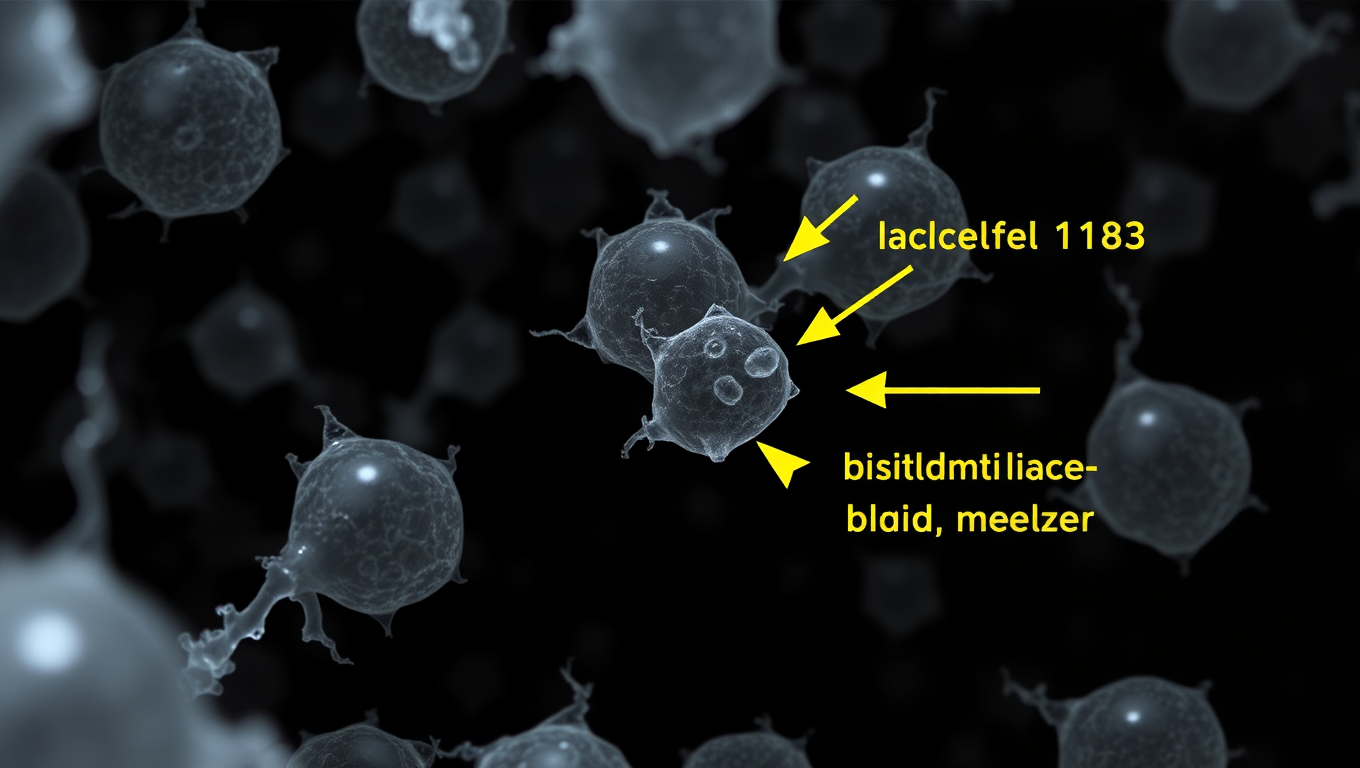

Scientists Discover a Tiny Molecule That Could Revolutionize Weight Loss Treatment

Researchers at the Salk Institute have used CRISPR to uncover hidden microproteins that control fat cell growth and lipid storage, identifying one confirmed target, Adipocyte-smORF-1183. This breakthrough could lead to more effective obesity treatments, surpassing the limitations of current drugs like GLP-1.

Chronic Illness

Scientists Uncover Hidden Brain Shortcut for Weight Loss without Nausea

Scientists have uncovered a way to promote weight loss and improve blood sugar control without the unpleasant side effects of current GLP-1 drugs. By shifting focus from neurons to brain support cells that produce appetite-suppressing molecules, they developed a modified compound, TDN, that worked in animal tests without causing nausea or vomiting.

-

Detectors10 months ago

Detectors10 months agoA New Horizon for Vision: How Gold Nanoparticles May Restore People’s Sight

-

Earth & Climate12 months ago

Earth & Climate12 months agoRetiring Abroad Can Be Lonely Business

-

Cancer11 months ago

Cancer11 months agoRevolutionizing Quantum Communication: Direct Connections Between Multiple Processors

-

Albert Einstein12 months ago

Albert Einstein12 months agoHarnessing Water Waves: A Breakthrough in Controlling Floating Objects

-

Chemistry11 months ago

Chemistry11 months ago“Unveiling Hidden Patterns: A New Twist on Interference Phenomena”

-

Earth & Climate11 months ago

Earth & Climate11 months agoHousehold Electricity Three Times More Expensive Than Upcoming ‘Eco-Friendly’ Aviation E-Fuels, Study Reveals

-

Diseases and Conditions12 months ago

Diseases and Conditions12 months agoReducing Falls Among Elderly Women with Polypharmacy through Exercise Intervention

-

Agriculture and Food11 months ago

Agriculture and Food11 months ago“A Sustainable Solution: Researchers Create Hybrid Cheese with 25% Pea Protein”