While we try to keep things accurate, this content is part of an ongoing experiment and may not always be reliable.

Please double-check important details — we’re not responsible for how the information is used.

Behavioral Science

Early Detection of Wood Coating Deterioration: A Data-Driven Approach to Sustainable Building Maintenance

From the Japanese cypress to the ponderosa pine, wood has been used in construction for millennia. Though materials like steel and concrete have largely taken over large building construction, wood is making a comeback, increasingly being used in public and multi-story buildings for its environmental benefits. Of course, wood has often been passed over in favor of other materials because it is easily damaged by sunlight and moisture when used outdoors. Wood coatings have been designed to protect wood surfaces for this reason, but coating damage often starts before it becomes visible. Once the deterioration can be seen with the naked eye, it is already too late. To solve this problem, a team of researchers is working to create a simple but effective method of diagnosing this nearly invisible deterioration before the damage becomes irreparable.

Behavioral Science

“Rewired for Romance: Scientists Give Gift-Giving Behavior to Singing Fruit Flies”

By flipping a single genetic switch, researchers made one fruit fly species adopt the gift-giving courtship of another, showing how tiny brain rewiring can drive evolutionary change.

Behavioral Science

The Amazing Ant Strategy That Can Revolutionize Robotics

Weaver ants have cracked a teamwork puzzle that humans have struggled with for over a century — instead of slacking off as their group grows, they work harder. These tiny architects not only build elaborate leaf nests but also double their pulling power when more ants join in. Using a “force ratchet” system where some pull while others anchor, they outperform the efficiency of human teams and could inspire revolutionary advances in robotics cooperation.

Alternative Medicine

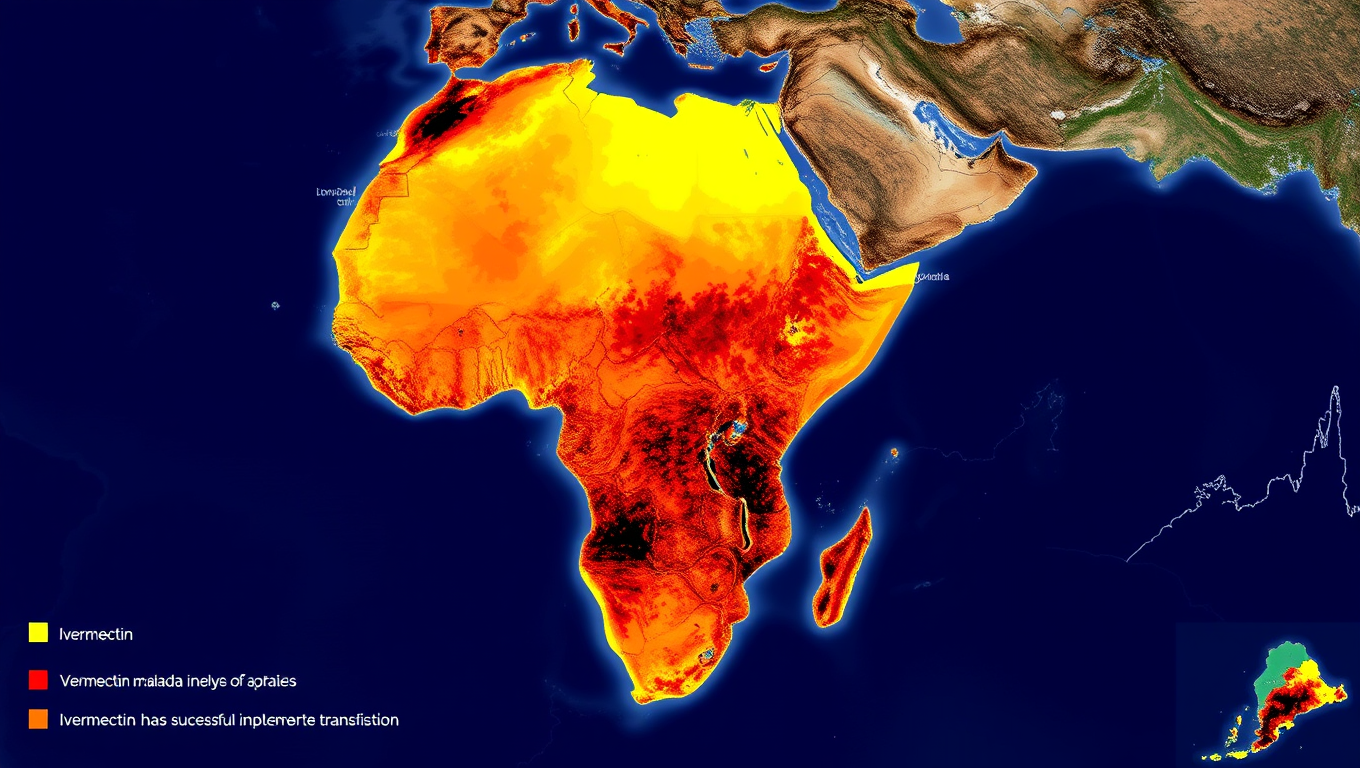

Ivermectin: The Mosquito-Killing Pill That Dropped Malaria by 26%

A groundbreaking study has revealed that the mass administration of ivermectin—a drug once known for treating river blindness and scabies—can significantly reduce malaria transmission when used in conjunction with bed nets.

-

Detectors10 months ago

Detectors10 months agoA New Horizon for Vision: How Gold Nanoparticles May Restore People’s Sight

-

Earth & Climate11 months ago

Earth & Climate11 months agoRetiring Abroad Can Be Lonely Business

-

Cancer11 months ago

Cancer11 months agoRevolutionizing Quantum Communication: Direct Connections Between Multiple Processors

-

Albert Einstein11 months ago

Albert Einstein11 months agoHarnessing Water Waves: A Breakthrough in Controlling Floating Objects

-

Chemistry10 months ago

Chemistry10 months ago“Unveiling Hidden Patterns: A New Twist on Interference Phenomena”

-

Earth & Climate11 months ago

Earth & Climate11 months agoHousehold Electricity Three Times More Expensive Than Upcoming ‘Eco-Friendly’ Aviation E-Fuels, Study Reveals

-

Agriculture and Food11 months ago

Agriculture and Food11 months ago“A Sustainable Solution: Researchers Create Hybrid Cheese with 25% Pea Protein”

-

Diseases and Conditions11 months ago

Diseases and Conditions11 months agoReducing Falls Among Elderly Women with Polypharmacy through Exercise Intervention