While we try to keep things accurate, this content is part of an ongoing experiment and may not always be reliable.

Please double-check important details — we’re not responsible for how the information is used.

Earth & Climate

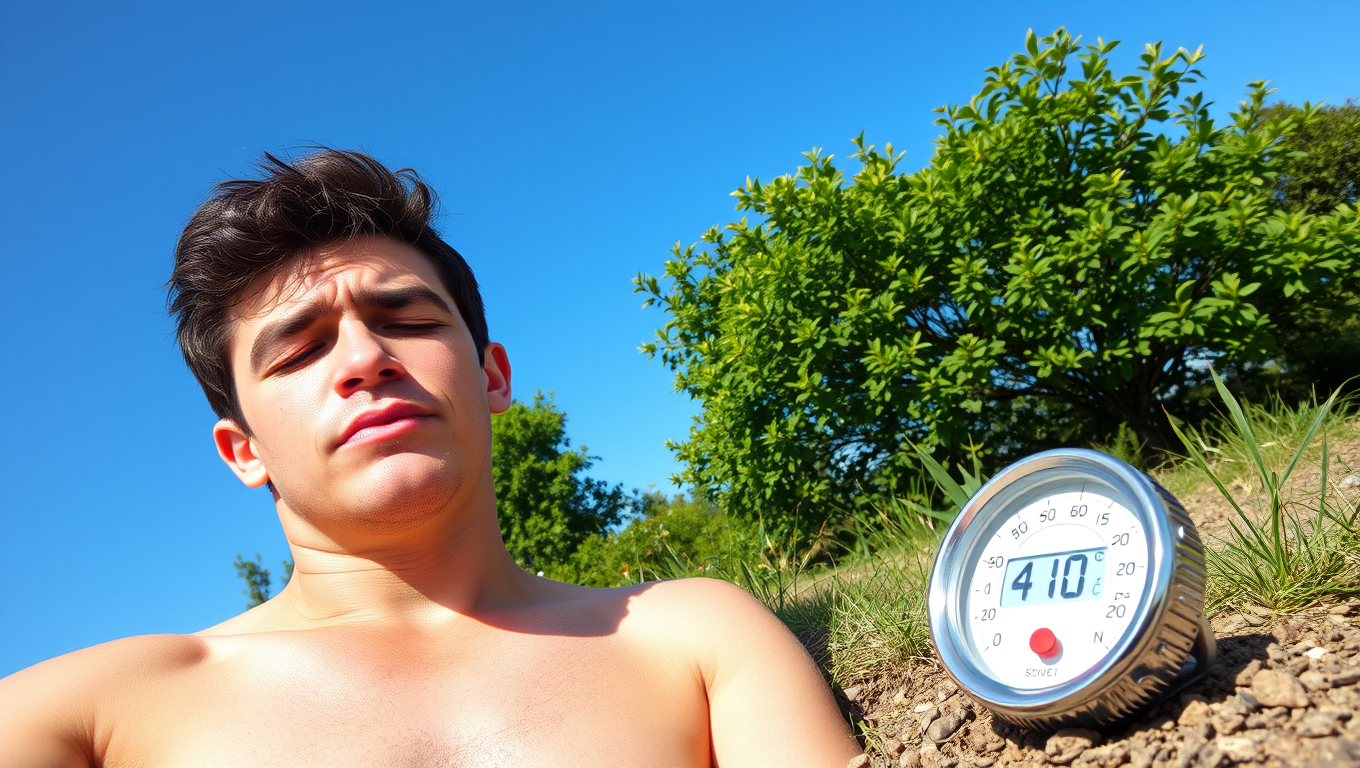

New Study Validates Lower Limits of Human Heat Tolerance: A Wake-Up Call for Climate Action

Human thermoregulation limits are lower than previously thought, indicating that some regions may soon experience heat and humidity levels exceeding safe limits for survival. The study underscores the urgent need to address climate change impacts on human health, providing vital data to inform public health strategies and climate models.

Dogs

“Dogs as Conservation Detectives: Unleashing the Power of Citizen Scientists in Fighting Invasive Species”

Dogs trained by everyday pet owners are proving to be surprisingly powerful allies in the fight against the invasive spotted lanternfly. In a groundbreaking study, citizen scientists taught their dogs to sniff out the pests’ hard-to-spot egg masses with impressive accuracy. The initiative not only taps into the huge community of recreational scent-detection dog enthusiasts, but also opens a promising new front in protecting agriculture. And it doesn’t stop there—these canine teams are now sniffing out vineyard diseases too, hinting at a whole new future of four-legged fieldwork.

Earth & Climate

“Wildfires Don’t Scare Them Off: Jaguars Thrive in Refuges After Brazil’s Blazes”

After devastating wildfires scorched the Brazilian Pantanal, an unexpected phenomenon unfolded—more jaguars began arriving at a remote wetland already known for having the densest jaguar population on Earth. Scientists discovered that not only did the local jaguars survive, but their numbers swelled as migrants sought refuge. This unique ecosystem, where jaguars feast mainly on fish and caimans and tolerate each other’s presence unusually well, proved remarkably resilient. Researchers found that this floodplain may serve as a natural climate sanctuary, highlighting its crucial role in a changing world.

Earth & Climate

The Hidden Threat to Hawaii’s Coral Reefs: A Climate Crisis Unfolds

Hawaiian coral reefs may face unprecedented ocean acidification within 30 years, driven by carbon emissions. A new study by University of Hawai‘i researchers shows that even under conservative climate scenarios, nearshore waters will change more drastically than reefs have experienced in thousands of years. Some coral species may adapt, offering a glimmer of hope, but others may face critical stress.

-

Detectors3 months ago

Detectors3 months agoA New Horizon for Vision: How Gold Nanoparticles May Restore People’s Sight

-

Earth & Climate4 months ago

Earth & Climate4 months agoRetiring Abroad Can Be Lonely Business

-

Cancer4 months ago

Cancer4 months agoRevolutionizing Quantum Communication: Direct Connections Between Multiple Processors

-

Agriculture and Food4 months ago

Agriculture and Food4 months ago“A Sustainable Solution: Researchers Create Hybrid Cheese with 25% Pea Protein”

-

Diseases and Conditions4 months ago

Diseases and Conditions4 months agoReducing Falls Among Elderly Women with Polypharmacy through Exercise Intervention

-

Albert Einstein4 months ago

Albert Einstein4 months agoHarnessing Water Waves: A Breakthrough in Controlling Floating Objects

-

Chemistry4 months ago

Chemistry4 months ago“Unveiling Hidden Patterns: A New Twist on Interference Phenomena”

-

Earth & Climate4 months ago

Earth & Climate4 months agoHousehold Electricity Three Times More Expensive Than Upcoming ‘Eco-Friendly’ Aviation E-Fuels, Study Reveals