While we try to keep things accurate, this content is part of an ongoing experiment and may not always be reliable.

Please double-check important details — we’re not responsible for how the information is used.

Dolphins and Whales

Uncovering Ancient Whales: The Oldest Known Whale Bone Tools Revealed

Humans were making tools from whale bones as far back as 20,000 years ago, according to a new study. This discovery broadens our understanding of early human use of whale remains and offers valuable insight into the marine ecology of the time.

Dolphins and Whales

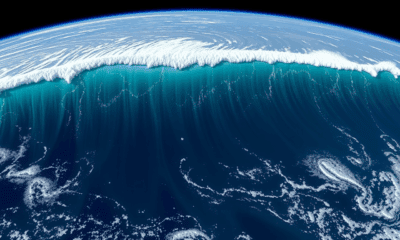

The Unrelenting Impact of Marine Heatwaves: Shattering Ecosystems, Starving Whales, and Driving Fish North

A scorching marine heatwave from 2014 to 2016 devastated the Pacific coast, shaking ecosystems from plankton to whales and triggering mass die-offs, migrations, and fishery collapses. Researchers synthesized findings from over 300 studies, revealing the far-reaching impacts of rising ocean temperatures. Kelp forests withered, species shifted north, and iconic marine animals perished—offering a chilling preview of the future oceans under climate change. This sweeping event calls for urgent action in marine conservation and climate mitigation.

Dolphins and Whales

The Hidden Risks of Deep-Sea Mining: Protecting Whales and Dolphins from Underwater Noise Pollution

Exploration for deep-sea minerals in the Clarion Clipperton Zone threatens to disrupt an unexpectedly rich ecosystem of whales and dolphins. New studies have detected endangered species in the area and warn that mining noise and sediment could devastate marine life that relies heavily on sound. With so little known about these habitats, experts urge immediate assessment of the risks.

Animal Learning and Intelligence

Whales Speak Their Minds: Decoding the Secret Language of Bubble Rings

Humpback whales have been observed blowing bubble rings during friendly interactions with humans a behavior never before documented. This surprising display may be more than play; it could represent a sophisticated form of non-verbal communication. Scientists from the SETI Institute and UC Davis believe these interactions offer valuable insights into non-human intelligence, potentially helping refine our methods for detecting extraterrestrial life. Their findings underscore the intelligence, curiosity, and social complexity of whales, making them ideal analogues for developing communication models beyond Earth.

-

Detectors9 months ago

Detectors9 months agoA New Horizon for Vision: How Gold Nanoparticles May Restore People’s Sight

-

Earth & Climate10 months ago

Earth & Climate10 months agoRetiring Abroad Can Be Lonely Business

-

Cancer10 months ago

Cancer10 months agoRevolutionizing Quantum Communication: Direct Connections Between Multiple Processors

-

Albert Einstein10 months ago

Albert Einstein10 months agoHarnessing Water Waves: A Breakthrough in Controlling Floating Objects

-

Chemistry10 months ago

Chemistry10 months ago“Unveiling Hidden Patterns: A New Twist on Interference Phenomena”

-

Earth & Climate10 months ago

Earth & Climate10 months agoHousehold Electricity Three Times More Expensive Than Upcoming ‘Eco-Friendly’ Aviation E-Fuels, Study Reveals

-

Agriculture and Food10 months ago

Agriculture and Food10 months ago“A Sustainable Solution: Researchers Create Hybrid Cheese with 25% Pea Protein”

-

Diseases and Conditions10 months ago

Diseases and Conditions10 months agoReducing Falls Among Elderly Women with Polypharmacy through Exercise Intervention