While we try to keep things accurate, this content is part of an ongoing experiment and may not always be reliable.

Please double-check important details — we’re not responsible for how the information is used.

Biology

Uncovering the Ground-Breaking Habits of Ancient Flying Reptiles

A new study links fossilized flying reptile tracks to animals that made them. Fossilized footprints reveal a 160-million-year-old invasion as pterosaurs came down from the trees and onto the ground. Tracks of giant ground-stalkers, comb-jawed coastal waders, and specialized shell crushers, shed light on how pterosaurs lived, moved, and evolved.

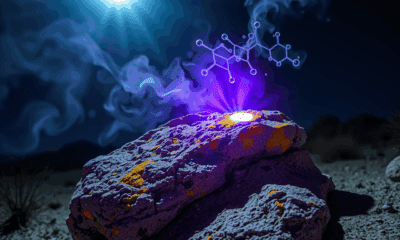

Bacteria

Unveiling the Secrets of Pandoraea: How Lung Bacteria Forge Iron-Stealing Weapons to Survive

Researchers investigating the enigmatic and antibiotic-resistant Pandoraea bacteria have uncovered a surprising twist: these pathogens don’t just pose risks they also produce powerful natural compounds. By studying a newly discovered gene cluster called pan, scientists identified two novel molecules Pandorabactin A and B that allow the bacteria to steal iron from their environment, giving them a survival edge in iron-poor places like the human body. These molecules also sabotage rival bacteria by starving them of iron, potentially reshaping microbial communities in diseases like cystic fibrosis.

Animals

“Red Vision Unlocked: Mediterranean Beetles Shatter Insect Color Limitations”

Beetles that can see the color red? That s exactly what scientists discovered in two Mediterranean species that defy the norm of insect vision. While most insects are blind to red, these beetles use specialized photoreceptors to detect it and even show a strong preference for red flowers like poppies and anemones. This breakthrough challenges long-standing assumptions about how flower colors evolved and opens a new path for studying how pollinators influence plant traits over time.

Animals

“Revolutionizing Agriculture: Uncovering the Hidden Secrets of a Tiny Wasp’s Reproductive Trick”

Aphid-hunting wasps can reproduce with or without sex, challenging previous assumptions. This unique flexibility could boost sustainable pest control if its hidden drawbacks can be managed.

-

Detectors2 months ago

Detectors2 months agoA New Horizon for Vision: How Gold Nanoparticles May Restore People’s Sight

-

Earth & Climate4 months ago

Earth & Climate4 months agoRetiring Abroad Can Be Lonely Business

-

Cancer3 months ago

Cancer3 months agoRevolutionizing Quantum Communication: Direct Connections Between Multiple Processors

-

Agriculture and Food3 months ago

Agriculture and Food3 months ago“A Sustainable Solution: Researchers Create Hybrid Cheese with 25% Pea Protein”

-

Diseases and Conditions4 months ago

Diseases and Conditions4 months agoReducing Falls Among Elderly Women with Polypharmacy through Exercise Intervention

-

Earth & Climate3 months ago

Earth & Climate3 months agoHousehold Electricity Three Times More Expensive Than Upcoming ‘Eco-Friendly’ Aviation E-Fuels, Study Reveals

-

Chemistry3 months ago

Chemistry3 months ago“Unveiling Hidden Patterns: A New Twist on Interference Phenomena”

-

Albert Einstein4 months ago

Albert Einstein4 months agoHarnessing Water Waves: A Breakthrough in Controlling Floating Objects