While we try to keep things accurate, this content is part of an ongoing experiment and may not always be reliable.

Please double-check important details — we’re not responsible for how the information is used.

Endangered Animals

Unlocking the Secrets of Rainbow Reefs: Uncovering the Ancient Origins of Glowing Fish

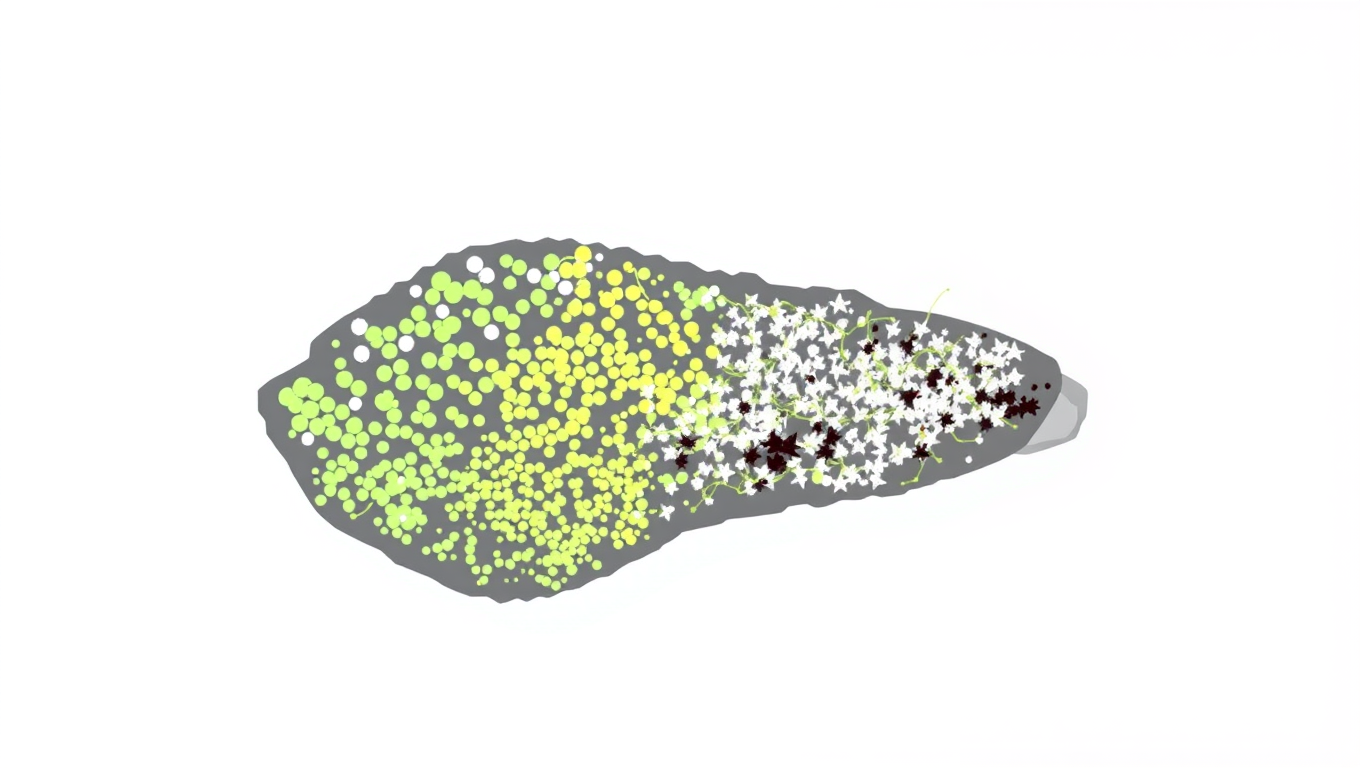

Scientists have uncovered that fish biofluorescence a captivating ability to glow in vivid colors has ancient roots stretching back over 100 million years. This trait evolved independently in reef fish more than 100 times, likely influenced by post-dinosaur-extinction reef expansion. The glowing spectacle is more diverse than previously imagined, spanning multiple colors across hundreds of species.

Earth & Climate

Hidden Crisis Uncovered: Ancient Bird Droppings Reveal Widespread Parasite Extinctions

An intriguing new study reveals that over 80% of parasites found in the ancient poo of New Zealand’s endangered kākāpō have vanished, even though the bird itself is still hanging on. Researchers discovered this dramatic parasite decline by analyzing droppings dating back 1,500 years, uncovering an unexpected wave of coextinctions that occurred long before recent conservation efforts began. These hidden losses suggest that as we fight to save charismatic species, we may be silently erasing whole communities of organisms that play crucial, yet misunderstood, ecological roles.

Earth & Climate

Unveiling Hidden Populations: Drones Reveal 41,000-Turtle Nesting Site in Amazon Rainforest

A team at the University of Florida used drones and smart modeling to accurately count over 41,000 endangered turtles nesting along the Amazon’s Guaporé River—revealing the world’s largest known turtle nesting site. Their innovative technique, combining aerial imagery with statistical correction for turtle movement, exposes major flaws in traditional counting methods and opens doors to more precise wildlife monitoring worldwide.

Ecology Research

The Dangers of Human Interactions with Wildlife: A Threat to Elephants and Humans Alike

Tourists feeding wild elephants may seem innocent or even compassionate, but a new 18-year study reveals it s a recipe for disaster. Elephants in Sri Lanka and India have learned to beg for snacks sugary treats and human food leading to deadly encounters, injuries, and even the ingestion of plastic. Once wild animals become accustomed to handouts, they lose their natural instincts, grow bolder, and risk both their lives and the safety of humans.

-

Detectors10 months ago

Detectors10 months agoA New Horizon for Vision: How Gold Nanoparticles May Restore People’s Sight

-

Earth & Climate12 months ago

Earth & Climate12 months agoRetiring Abroad Can Be Lonely Business

-

Cancer11 months ago

Cancer11 months agoRevolutionizing Quantum Communication: Direct Connections Between Multiple Processors

-

Albert Einstein12 months ago

Albert Einstein12 months agoHarnessing Water Waves: A Breakthrough in Controlling Floating Objects

-

Chemistry11 months ago

Chemistry11 months ago“Unveiling Hidden Patterns: A New Twist on Interference Phenomena”

-

Earth & Climate11 months ago

Earth & Climate11 months agoHousehold Electricity Three Times More Expensive Than Upcoming ‘Eco-Friendly’ Aviation E-Fuels, Study Reveals

-

Agriculture and Food11 months ago

Agriculture and Food11 months ago“A Sustainable Solution: Researchers Create Hybrid Cheese with 25% Pea Protein”

-

Diseases and Conditions12 months ago

Diseases and Conditions12 months agoReducing Falls Among Elderly Women with Polypharmacy through Exercise Intervention