While we try to keep things accurate, this content is part of an ongoing experiment and may not always be reliable.

Please double-check important details — we’re not responsible for how the information is used.

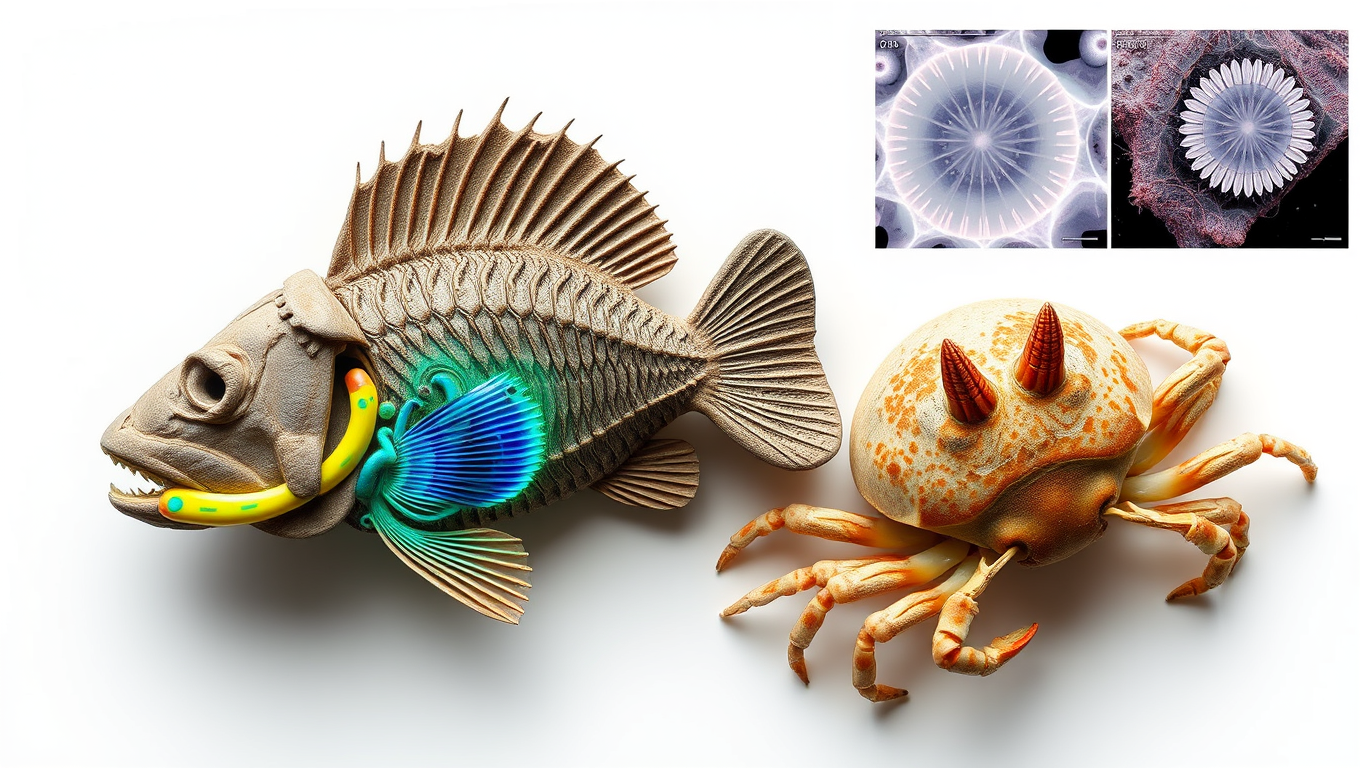

Dentistry

The Ancient Origin of Teeth and Sensory Exoskeletons Revealed

New research shows that dentine, the inner layer of teeth that transmits sensory information to nerves inside the pulp, first evolved as sensory tissue in the armored exoskeletons of ancient fish.

Allergy

Flossing for Vaccines: A New Method to Deliver Immunizations

Scientists have discovered that flossing between your teeth could one day help vaccinate you. By targeting a uniquely permeable gum tissue called the junctional epithelium, this new method stimulates immunity right where many infections enter: the mouth, nose, and lungs. Using dental floss on mice to apply a flu vaccine triggered a robust immune response—better than existing oral approaches and comparable to nasal vaccines, but without the risks. It even worked with mRNA and protein-based vaccines.

Ancient Civilizations

Uncovering Ancient Highs: 4,000-Year-Old Teeth Reveal Earliest Human Psychoactive Plant Use

Scientists have discovered the oldest direct evidence of betel nut chewing in Southeast Asia by analyzing 4,000-year-old dental plaque from a burial in Thailand. This breakthrough method reveals invisible traces of ancient plant use, suggesting psychoactive rituals were part of daily life long before written records.

Ancient Civilizations

The Ancient Roots of Disease: Scientists Uncover 214 Prehistoric Pathogens in Human DNA

Scientists have uncovered DNA from 214 ancient pathogens in prehistoric humans, including the oldest known evidence of plague. The findings show zoonotic diseases began spreading around 6,500 years ago, likely triggered by farming and animal domestication. These ancient infections may still influence us today, and help guide the vaccines of tomorrow.

-

Detectors9 months ago

Detectors9 months agoA New Horizon for Vision: How Gold Nanoparticles May Restore People’s Sight

-

Earth & Climate10 months ago

Earth & Climate10 months agoRetiring Abroad Can Be Lonely Business

-

Cancer10 months ago

Cancer10 months agoRevolutionizing Quantum Communication: Direct Connections Between Multiple Processors

-

Albert Einstein10 months ago

Albert Einstein10 months agoHarnessing Water Waves: A Breakthrough in Controlling Floating Objects

-

Chemistry10 months ago

Chemistry10 months ago“Unveiling Hidden Patterns: A New Twist on Interference Phenomena”

-

Earth & Climate10 months ago

Earth & Climate10 months agoHousehold Electricity Three Times More Expensive Than Upcoming ‘Eco-Friendly’ Aviation E-Fuels, Study Reveals

-

Agriculture and Food10 months ago

Agriculture and Food10 months ago“A Sustainable Solution: Researchers Create Hybrid Cheese with 25% Pea Protein”

-

Diseases and Conditions10 months ago

Diseases and Conditions10 months agoReducing Falls Among Elderly Women with Polypharmacy through Exercise Intervention