While we try to keep things accurate, this content is part of an ongoing experiment and may not always be reliable.

Please double-check important details — we’re not responsible for how the information is used.

Dinosaurs

Uncovering a Microscopic Spear: Fossil Record Reveals 160 Million-Year-Old Fungus Piercing Trees

In a paper published in National Science Review, a Chinese team of scientists highlights the discovery of well-preserved blue-stain fungal hyphae within a Jurassic fossil wood from northeastern China, which pushes back the earliest known fossil record of this fungal group by approximately 80 million years. The new finding provides crucial fossil evidence for studying the origin and early evolution of blue-stain fungi and offers fresh insights into understanding the ecological relationships between the blue-stain fungi, plants, and insects during the Jurassic period.

Animals

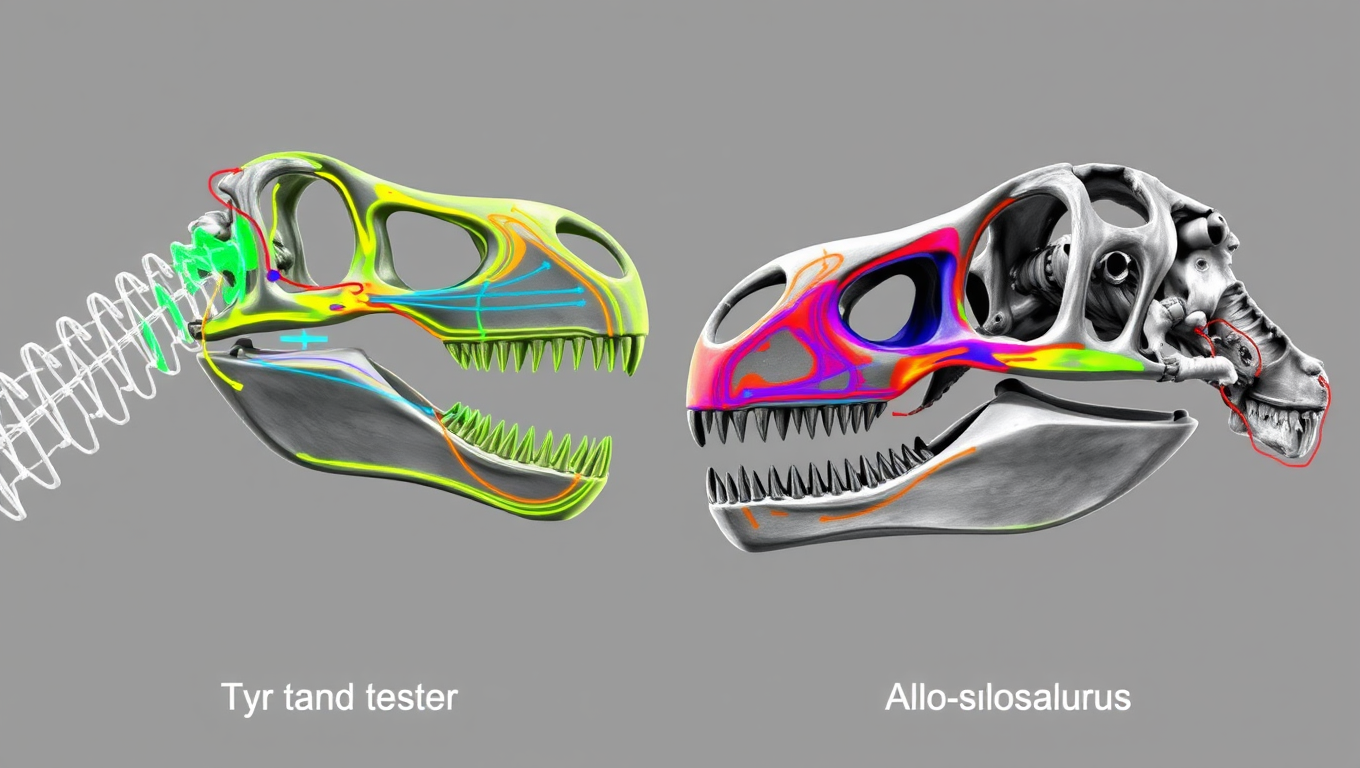

Crushing vs. Slashing: New Skull Scans Reveal How Giant Dinosaurs Hunted Prey

Tyrannosaurus rex might be the most famous meat-eater of all time, but it turns out it wasn’t the only way to be a terrifying giant. New research shows that while T. rex evolved a skull designed for bone-crushing bites like a modern crocodile, other massive carnivorous dinosaurs like spinosaurs and allosaurs took a very different route — specializing in slashing and tearing flesh instead.

Ancient DNA

Rewriting a 400-million-year-old fish’s tale: Uncovering new insights into vertebrate evolution.

A fish thought to be evolution’s time capsule just surprised scientists. A detailed dissection of the coelacanth — a 400-million-year-old species often called a “living fossil” — revealed that key muscles believed to be part of early vertebrate evolution were actually misidentified ligaments. This means foundational assumptions about how vertebrates, including humans, evolved to eat and breathe may need to be rewritten. The discovery corrects decades of anatomical errors, reshapes the story of skull evolution, and brings unexpected insights into our own distant origins.

Ancient Civilizations

Unveiling North America’s Oldest Pterosaur: A Triassic Time Capsule Reveals a Diverse Ecosystem

In the remote reaches of Arizona s Petrified Forest National Park, scientists have unearthed North America’s oldest known pterosaur a small, gull-sized flier that once soared above Triassic ecosystems. This exciting find, alongside ancient turtles and armored amphibians, sheds light on a key moment in Earth’s history when older animal groups overlapped with evolutionary newcomers. The remarkably preserved fossils, including over 1,200 specimens, offer a rare glimpse into a vibrant world just before a mass extinction reshaped life on Earth.

-

Detectors10 months ago

Detectors10 months agoA New Horizon for Vision: How Gold Nanoparticles May Restore People’s Sight

-

Earth & Climate12 months ago

Earth & Climate12 months agoRetiring Abroad Can Be Lonely Business

-

Cancer11 months ago

Cancer11 months agoRevolutionizing Quantum Communication: Direct Connections Between Multiple Processors

-

Albert Einstein12 months ago

Albert Einstein12 months agoHarnessing Water Waves: A Breakthrough in Controlling Floating Objects

-

Chemistry11 months ago

Chemistry11 months ago“Unveiling Hidden Patterns: A New Twist on Interference Phenomena”

-

Earth & Climate11 months ago

Earth & Climate11 months agoHousehold Electricity Three Times More Expensive Than Upcoming ‘Eco-Friendly’ Aviation E-Fuels, Study Reveals

-

Agriculture and Food11 months ago

Agriculture and Food11 months ago“A Sustainable Solution: Researchers Create Hybrid Cheese with 25% Pea Protein”

-

Diseases and Conditions12 months ago

Diseases and Conditions12 months agoReducing Falls Among Elderly Women with Polypharmacy through Exercise Intervention