While we try to keep things accurate, this content is part of an ongoing experiment and may not always be reliable.

Please double-check important details — we’re not responsible for how the information is used.

Animals

A Universal Antivenom: Scientists Develop Broadly Effective Treatment Against World’s Deadliest Snakes

By using antibodies from a human donor with a self-induced hyper-immunity to snake venom, scientists have developed the most broadly effective antivenom to date, which is protective against the likes of the black mamba, king cobra, and tiger snakes in mouse trials. The antivenom combines protective antibodies and a small molecule inhibitor and opens a path toward a universal antiserum.

Agriculture and Food

“Stronger Social Ties, Stronger Babies: How Female Friendships Help Chimpanzee Infants Survive”

Female chimpanzees that forge strong, grooming-rich friendships with other females dramatically boost their infants’ odds of making it past the perilous first year—no kin required. Three decades of Gombe observations show that well-integrated mothers enjoy a survival rate of up to 95% for their young, regardless of male allies or sisters. The payoff may come from shared defense, reduced stress, or better access to food, hinting that such alliances laid early groundwork for humanity’s extraordinary cooperative spirit.

Animal Learning and Intelligence

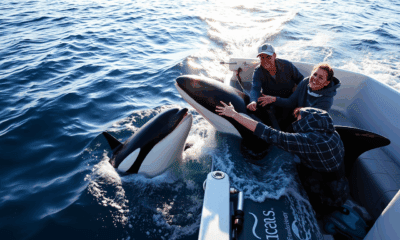

The Generous Giants: Unpacking the Mystery of Killer Whales Sharing Fish with Humans

Wild orcas across four continents have repeatedly floated fish and other prey to astonished swimmers and boaters, hinting that the ocean’s top predator likes to make friends. Researchers cataloged 34 such gifts over 20 years, noting the whales often lingered expectantly—and sometimes tried again—after humans declined their offerings, suggesting a curious, relationship-building motive.

Agriculture and Food

The Sleeping Side Preference of Cats: A Survival Strategy?

Cats overwhelmingly choose to sleep on their left side, a habit researchers say could be tied to survival. This sleep position activates the brain’s right hemisphere upon waking, perfect for detecting danger and reacting swiftly. Left-side snoozing may be more than a preference; it might be evolution’s secret trick.

-

Detectors3 months ago

Detectors3 months agoA New Horizon for Vision: How Gold Nanoparticles May Restore People’s Sight

-

Earth & Climate4 months ago

Earth & Climate4 months agoRetiring Abroad Can Be Lonely Business

-

Cancer3 months ago

Cancer3 months agoRevolutionizing Quantum Communication: Direct Connections Between Multiple Processors

-

Agriculture and Food4 months ago

Agriculture and Food4 months ago“A Sustainable Solution: Researchers Create Hybrid Cheese with 25% Pea Protein”

-

Diseases and Conditions4 months ago

Diseases and Conditions4 months agoReducing Falls Among Elderly Women with Polypharmacy through Exercise Intervention

-

Chemistry3 months ago

Chemistry3 months ago“Unveiling Hidden Patterns: A New Twist on Interference Phenomena”

-

Albert Einstein4 months ago

Albert Einstein4 months agoHarnessing Water Waves: A Breakthrough in Controlling Floating Objects

-

Earth & Climate3 months ago

Earth & Climate3 months agoHousehold Electricity Three Times More Expensive Than Upcoming ‘Eco-Friendly’ Aviation E-Fuels, Study Reveals