While we try to keep things accurate, this content is part of an ongoing experiment and may not always be reliable.

Please double-check important details — we’re not responsible for how the information is used.

Evolution

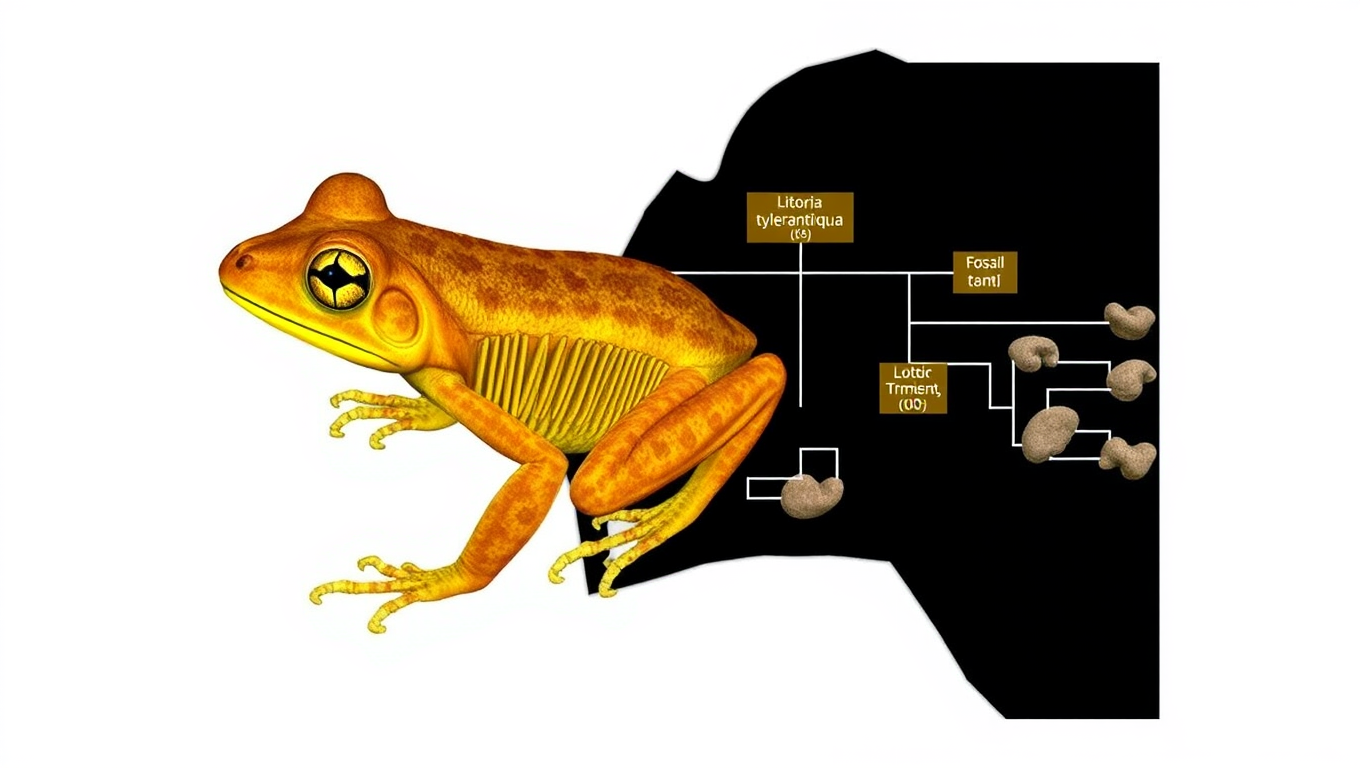

Australia’s Ancient Tree Frog Reveals 22 Million Years of Hidden History

Scientists have now discovered the oldest ancestor for all the Australian tree frogs, with distant links to the tree frogs of South America.

Early Humans

The Hidden Legacy of the Denisovans: Uncovering the Secrets of Human Evolution

Denisovans, a mysterious human relative, left behind far more than a handful of fossils—they left genetic fingerprints in modern humans across the globe. Multiple interbreeding events with distinct Denisovan populations helped shape traits like high-altitude survival in Tibetans, cold-weather adaptation in Inuits, and enhanced immunity. Their influence spanned from Siberia to South America, and scientists are now uncovering how these genetic gifts transformed human evolution, even with such limited physical remains.

Animals

Unveiling the Ancient Secrets of the Dirt Ant: A 16-million-year-old Fossil Reveals the Smallest Predator Ant Ever Found

A fossilized Caribbean dirt ant, Basiceros enana, preserved in Dominican amber, reveals the species ancient range and overturns assumptions about its size evolution. Advanced imaging shows it already had the camouflage adaptations of modern relatives, offering new insights into extinction and survival strategies.

Animals

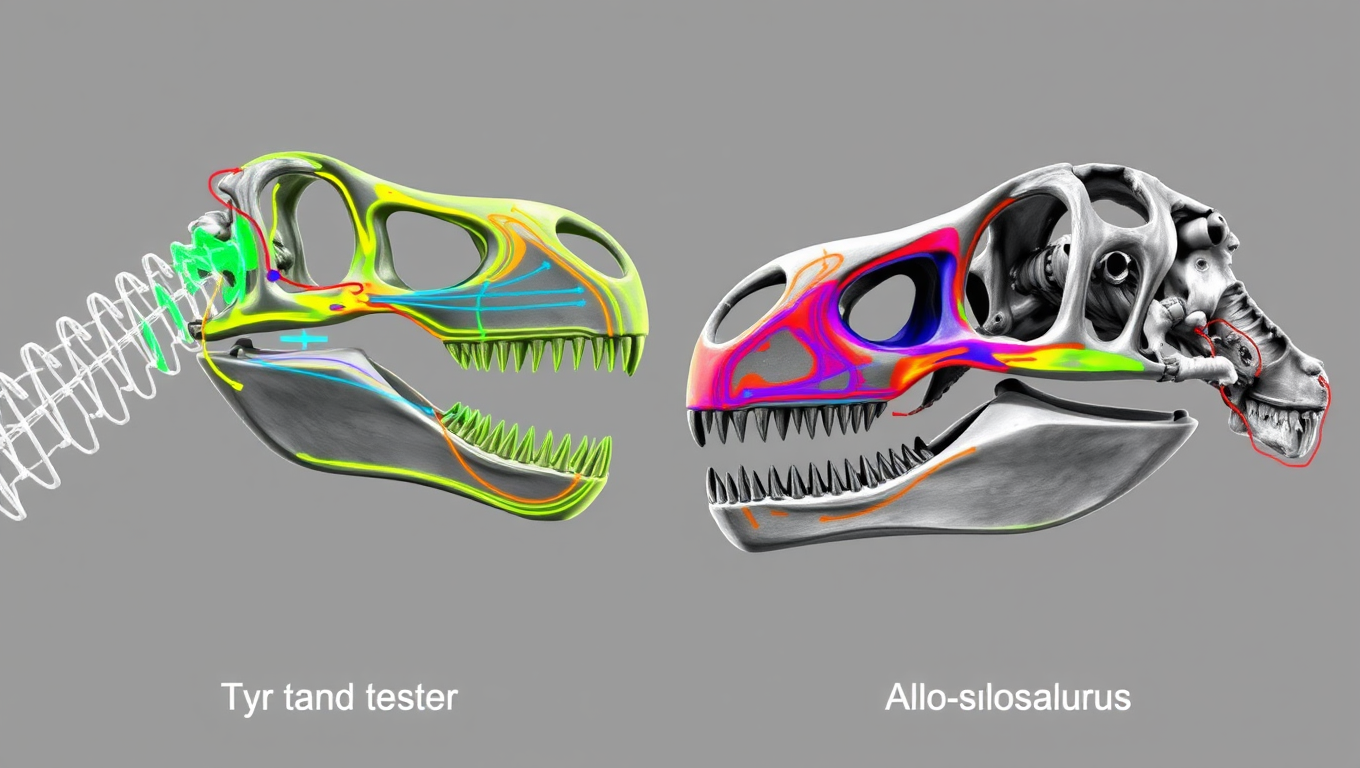

Crushing vs. Slashing: New Skull Scans Reveal How Giant Dinosaurs Hunted Prey

Tyrannosaurus rex might be the most famous meat-eater of all time, but it turns out it wasn’t the only way to be a terrifying giant. New research shows that while T. rex evolved a skull designed for bone-crushing bites like a modern crocodile, other massive carnivorous dinosaurs like spinosaurs and allosaurs took a very different route — specializing in slashing and tearing flesh instead.

-

Detectors10 months ago

Detectors10 months agoA New Horizon for Vision: How Gold Nanoparticles May Restore People’s Sight

-

Earth & Climate11 months ago

Earth & Climate11 months agoRetiring Abroad Can Be Lonely Business

-

Cancer10 months ago

Cancer10 months agoRevolutionizing Quantum Communication: Direct Connections Between Multiple Processors

-

Albert Einstein11 months ago

Albert Einstein11 months agoHarnessing Water Waves: A Breakthrough in Controlling Floating Objects

-

Chemistry10 months ago

Chemistry10 months ago“Unveiling Hidden Patterns: A New Twist on Interference Phenomena”

-

Earth & Climate10 months ago

Earth & Climate10 months agoHousehold Electricity Three Times More Expensive Than Upcoming ‘Eco-Friendly’ Aviation E-Fuels, Study Reveals

-

Agriculture and Food10 months ago

Agriculture and Food10 months ago“A Sustainable Solution: Researchers Create Hybrid Cheese with 25% Pea Protein”

-

Diseases and Conditions11 months ago

Diseases and Conditions11 months agoReducing Falls Among Elderly Women with Polypharmacy through Exercise Intervention