While we try to keep things accurate, this content is part of an ongoing experiment and may not always be reliable.

Please double-check important details — we’re not responsible for how the information is used.

Diseases and Conditions

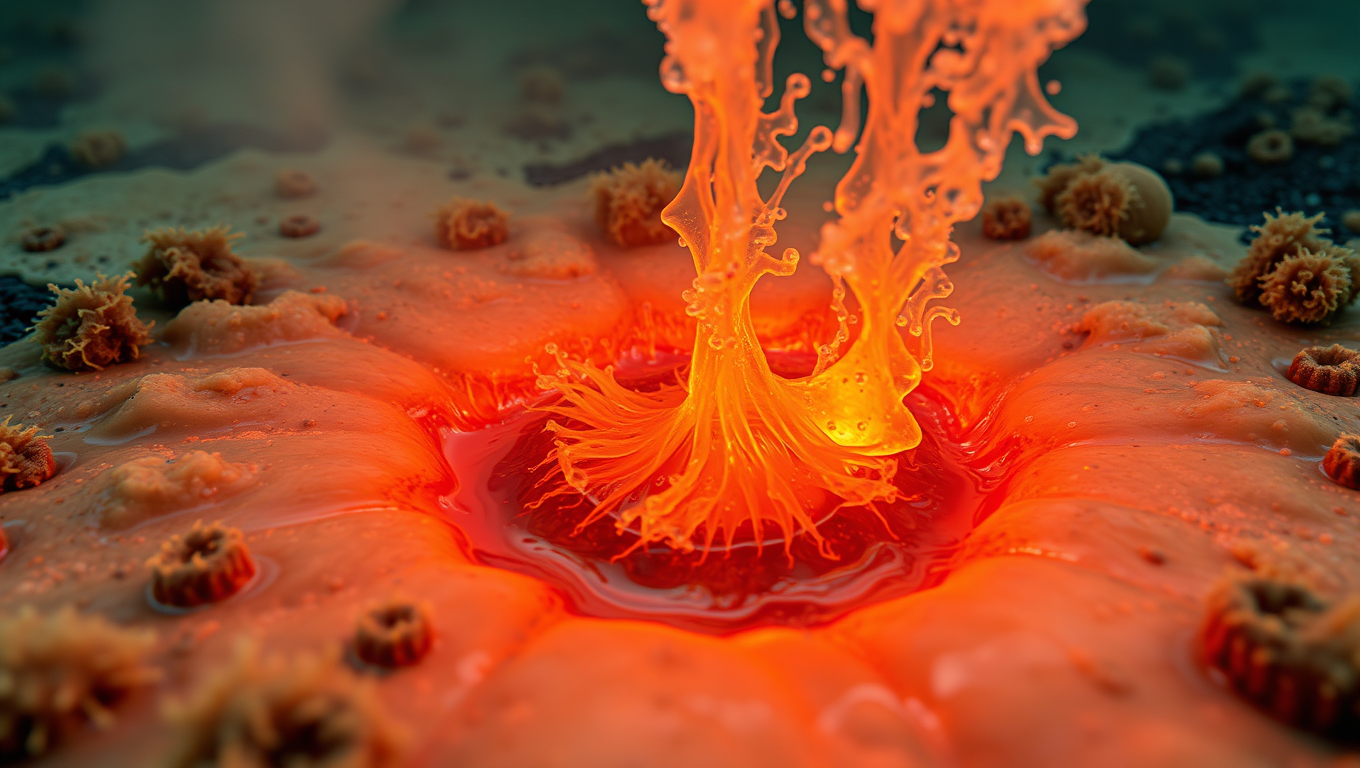

Microorganisms Unleash Their Secret Power in Extreme Environments

In the global carbon cycle microorganisms have evolved a variety of methods for fixing carbon. Researchers have investigated the methods that are utilized at extremely hot, acidic and sulfur-rich hydrothermal vents in shallow waters off the island of Kueishantao, Taiwan.

Animals

Florida Cat’s Latest Catch: New Virus Discovered in Shrew

A cat named Pepper has once again helped scientists discover a new virus—this time a mysterious orthoreovirus found in a shrew. Researchers from the University of Florida, including virologist John Lednicky, identified this strain during unrelated testing and published its genome. Although once thought to be harmless, these viruses are increasingly linked to serious diseases in humans and animals. With previous discoveries also pointing to a pattern of viral emergence in wildlife, scientists stress the need for more surveillance—and Pepper remains an unlikely but reliable viral scout.

Animals

The Lemur Secret to Aging without Inflammation: A Breakthrough for Human Health?

What if humans didn’t have to suffer the slow-burning fire of chronic inflammation as we age? A surprising study on two types of lemurs found no evidence of “inflammaging,” a phenomenon long assumed to be universal among primates. These findings suggest that age-related inflammation isn’t inevitable and that environmental factors could play a far bigger role than we thought. By peering into the biology of our primate cousins, researchers are opening up new possibilities for preventing aging-related diseases in humans.

Diet and Weight Loss

Rewiring the Brain: Scientists Develop Technique to Deliver Creatine Directly to the Brain

Creatine isn’t just for gym buffs; Virginia Tech scientists are using focused ultrasound to sneak this vital energy molecule past the blood-brain barrier, hoping to reverse devastating creatine transporter deficiencies. By momentarily opening microscopic gateways, they aim to revive brain growth and function without damaging healthy tissue—an approach that could fast-track from lab benches to lifesaving treatments.

-

Detectors3 months ago

Detectors3 months agoA New Horizon for Vision: How Gold Nanoparticles May Restore People’s Sight

-

Earth & Climate4 months ago

Earth & Climate4 months agoRetiring Abroad Can Be Lonely Business

-

Cancer4 months ago

Cancer4 months agoRevolutionizing Quantum Communication: Direct Connections Between Multiple Processors

-

Agriculture and Food4 months ago

Agriculture and Food4 months ago“A Sustainable Solution: Researchers Create Hybrid Cheese with 25% Pea Protein”

-

Diseases and Conditions4 months ago

Diseases and Conditions4 months agoReducing Falls Among Elderly Women with Polypharmacy through Exercise Intervention

-

Chemistry4 months ago

Chemistry4 months ago“Unveiling Hidden Patterns: A New Twist on Interference Phenomena”

-

Albert Einstein4 months ago

Albert Einstein4 months agoHarnessing Water Waves: A Breakthrough in Controlling Floating Objects

-

Earth & Climate4 months ago

Earth & Climate4 months agoHousehold Electricity Three Times More Expensive Than Upcoming ‘Eco-Friendly’ Aviation E-Fuels, Study Reveals