While we try to keep things accurate, this content is part of an ongoing experiment and may not always be reliable.

Please double-check important details — we’re not responsible for how the information is used.

Chronic Illness

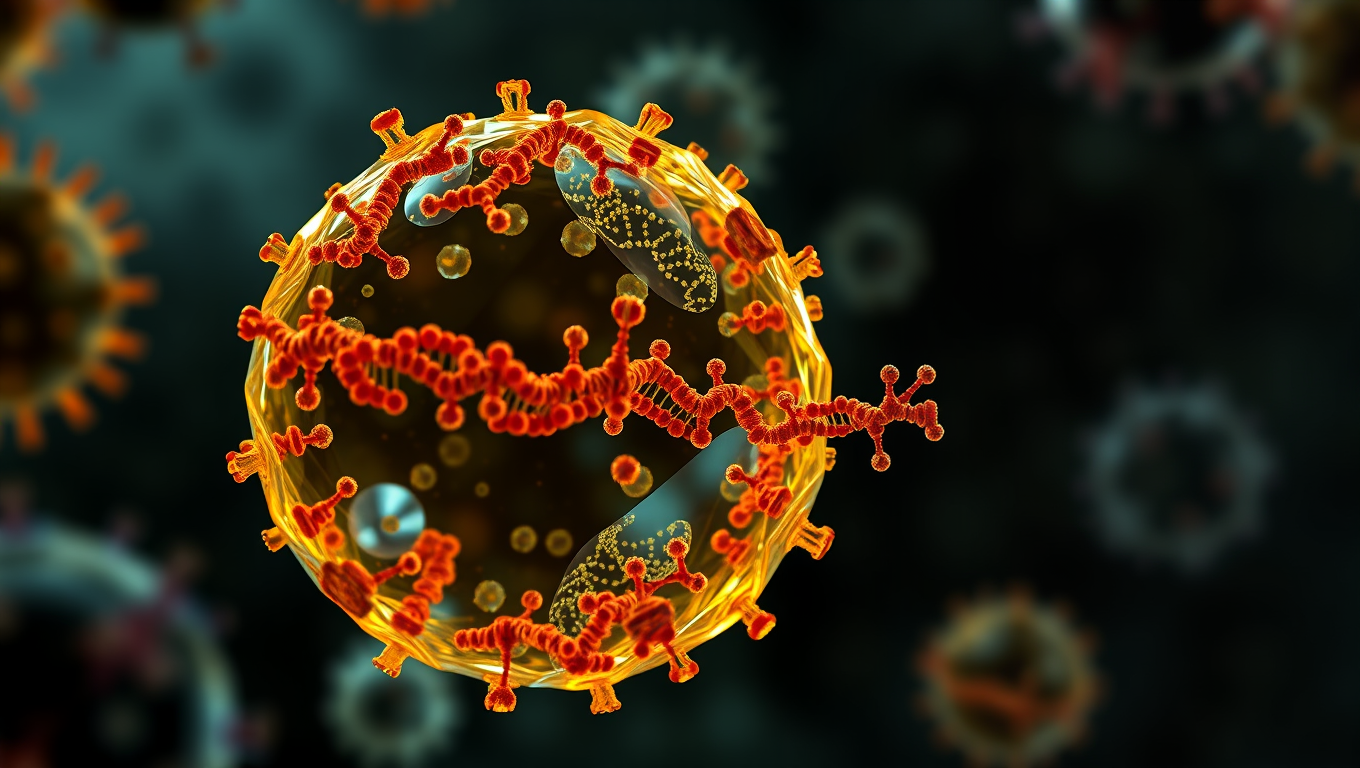

Mimicking Embryonic Growth to Break Barriers in Organoid Research

Organoids are made to model human organs and are promising for research and therapy, but there are limitations in their growth and function. A recent study found that placenta-derived IL1 under hypoxic conditions, can greatly increase growth of human stem cell-derived liver organoids. By promoting liver progenitor cell expansion through a specific signaling pathway, this method offers a promising route to improve organoid models and regenerative medicine.

Chronic Illness

Scientists Uncover Hidden Brain Shortcut for Weight Loss without Nausea

Scientists have uncovered a way to promote weight loss and improve blood sugar control without the unpleasant side effects of current GLP-1 drugs. By shifting focus from neurons to brain support cells that produce appetite-suppressing molecules, they developed a modified compound, TDN, that worked in animal tests without causing nausea or vomiting.

Cancer

A Silent Killer Unmasked: The Hidden Gene in Leukemia Virus that Could Revolutionize HIV Treatment

Scientists in Japan have discovered a genetic “silencer” within the HTLV-1 virus that helps it stay hidden in the body, evading the immune system for decades. This silencer element essentially turns the virus off, preventing it from triggering symptoms in most carriers. Incredibly, when this silencer was added to HIV, it made that virus less active too — hinting at a revolutionary new strategy for managing not just HTLV-1 but other deadly retroviruses as well. The discovery opens the door to turning the virus’s own stealth tactics against it in future treatments.

Chronic Illness

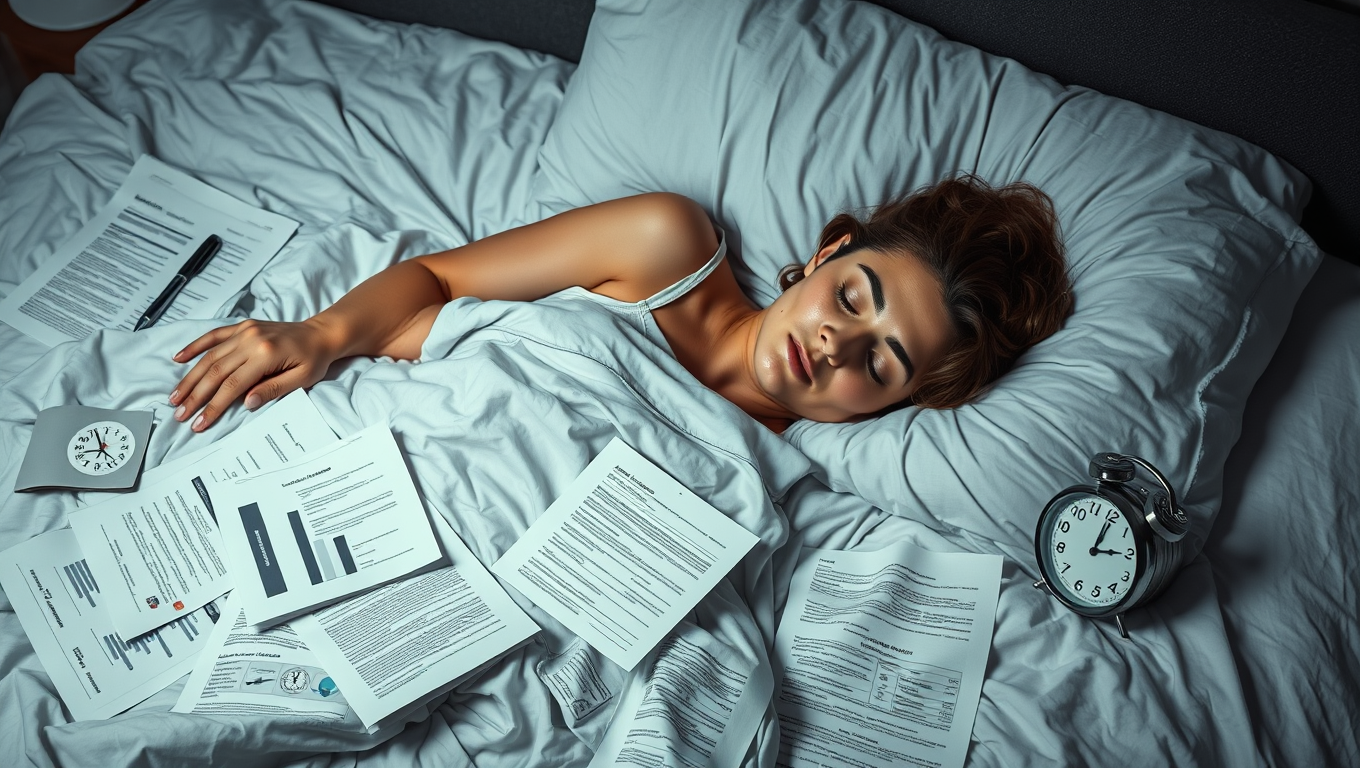

The Hidden Link Between Sleep Schedule and Disease Risk

A global study of over 88,000 adults reveals that poor sleep habits—like going to bed inconsistently or having disrupted circadian rhythms—are tied to dramatically higher risks for dozens of diseases, including liver cirrhosis and gangrene. Contrary to common belief, sleeping more than 9 hours wasn’t found to be harmful when measured objectively, exposing flaws in previous research. Scientists now say it’s time to redefine “good sleep” to include regularity, not just duration, as biological mechanisms like inflammation may underlie these powerful sleep-disease links.

-

Detectors10 months ago

Detectors10 months agoA New Horizon for Vision: How Gold Nanoparticles May Restore People’s Sight

-

Earth & Climate12 months ago

Earth & Climate12 months agoRetiring Abroad Can Be Lonely Business

-

Cancer11 months ago

Cancer11 months agoRevolutionizing Quantum Communication: Direct Connections Between Multiple Processors

-

Albert Einstein12 months ago

Albert Einstein12 months agoHarnessing Water Waves: A Breakthrough in Controlling Floating Objects

-

Chemistry11 months ago

Chemistry11 months ago“Unveiling Hidden Patterns: A New Twist on Interference Phenomena”

-

Earth & Climate11 months ago

Earth & Climate11 months agoHousehold Electricity Three Times More Expensive Than Upcoming ‘Eco-Friendly’ Aviation E-Fuels, Study Reveals

-

Agriculture and Food11 months ago

Agriculture and Food11 months ago“A Sustainable Solution: Researchers Create Hybrid Cheese with 25% Pea Protein”

-

Diseases and Conditions12 months ago

Diseases and Conditions12 months agoReducing Falls Among Elderly Women with Polypharmacy through Exercise Intervention