While we try to keep things accurate, this content is part of an ongoing experiment and may not always be reliable.

Please double-check important details — we’re not responsible for how the information is used.

Brain Tumor

Uncovering Cancer’s Weak Spots: How Mutations Can Make Chemotherapy Less Effective

Investigators have uncovered how resistance to chemotherapies may occur in some cancers. Researchers focused on a pathway that harnesses reactive oxygen species (ROS) to kill cancer cells. The study found that mutations to VPS35, a key player in this pathway, can prevent chemotherapy-induced cell death. These results could help pinpoint treatment-resistant tumors.

Brain Tumor

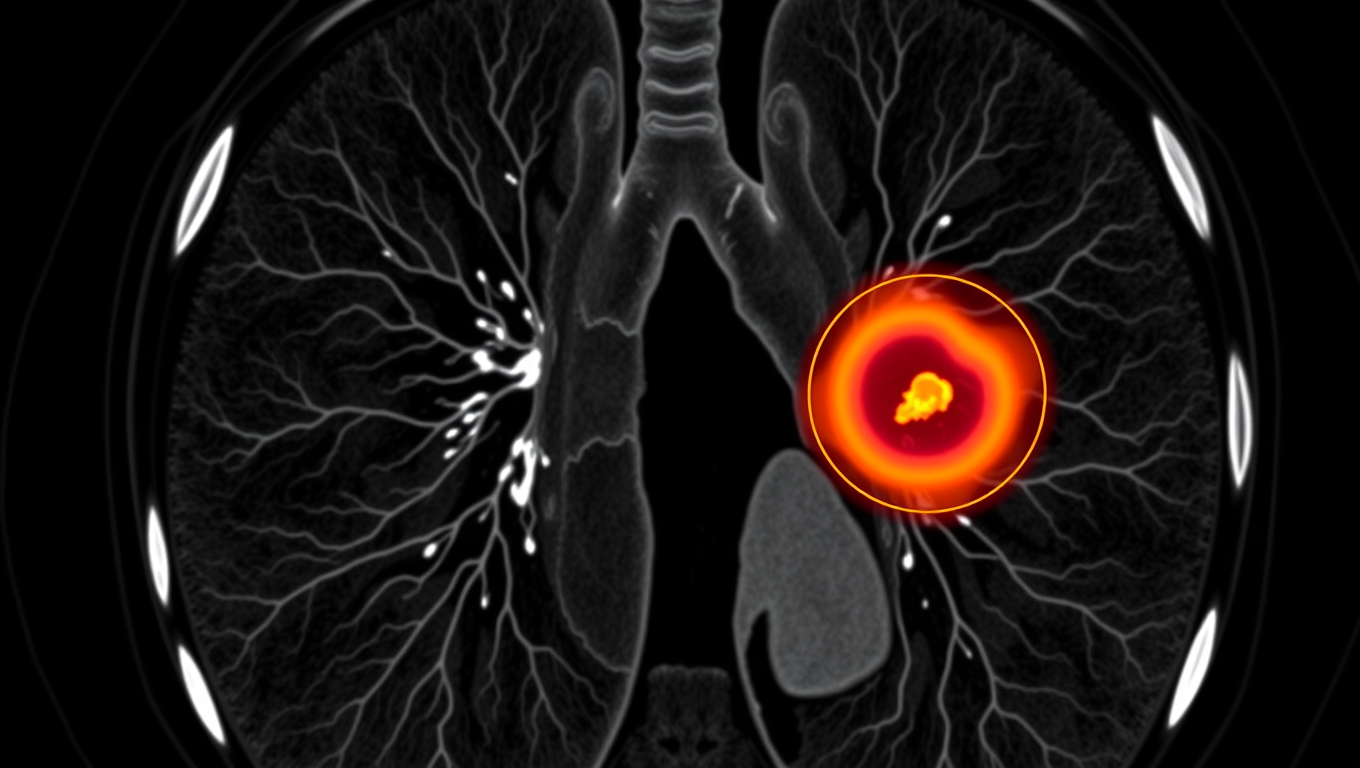

AI Tool Tracks Lung Tumors as You Breathe, Potentially Saving Lives

An AI system called iSeg is reshaping radiation oncology by automatically outlining lung tumors in 3D as they shift with each breath. Trained on scans from nine hospitals, the tool matched expert clinicians, flagged cancer zones some missed, and could speed up treatment planning while reducing deadly oversights.

Brain Injury

The Hidden Glitch Behind Hunger: Scientists Uncover the Brain Cells Responsible for Meal Memories

A team of scientists has identified specialized neurons in the brain that store “meal memories” detailed recollections of when and what we eat. These engrams, found in the ventral hippocampus, help regulate eating behavior by communicating with hunger-related areas of the brain. When these memory traces are impaired due to distraction, brain injury, or memory disorders individuals are more likely to overeat because they can’t recall recent meals. The research not only uncovers a critical neural mechanism but also suggests new strategies for treating obesity by enhancing memory around food consumption.

Brain Tumor

Uncovering Nature’s Secret: Ginger Compound Shows Promise in Targeting Cancer Cells’ Metabolism

Scientists in Japan have discovered that a natural compound found in a type of ginger called kencur can throw cancer cells into disarray by disrupting how they generate energy. While healthy cells use oxygen to make energy efficiently, cancer cells often rely on a backup method. This ginger-derived molecule doesn t attack that method directly it shuts down the cells’ fat-making machinery instead, which surprisingly causes the cells to ramp up their backup system even more. The finding opens new doors in the fight against cancer, showing how natural substances might help target cancer s hidden energy tricks.

-

Detectors10 months ago

Detectors10 months agoA New Horizon for Vision: How Gold Nanoparticles May Restore People’s Sight

-

Earth & Climate12 months ago

Earth & Climate12 months agoRetiring Abroad Can Be Lonely Business

-

Cancer11 months ago

Cancer11 months agoRevolutionizing Quantum Communication: Direct Connections Between Multiple Processors

-

Albert Einstein12 months ago

Albert Einstein12 months agoHarnessing Water Waves: A Breakthrough in Controlling Floating Objects

-

Chemistry11 months ago

Chemistry11 months ago“Unveiling Hidden Patterns: A New Twist on Interference Phenomena”

-

Earth & Climate11 months ago

Earth & Climate11 months agoHousehold Electricity Three Times More Expensive Than Upcoming ‘Eco-Friendly’ Aviation E-Fuels, Study Reveals

-

Diseases and Conditions12 months ago

Diseases and Conditions12 months agoReducing Falls Among Elderly Women with Polypharmacy through Exercise Intervention

-

Agriculture and Food11 months ago

Agriculture and Food11 months ago“A Sustainable Solution: Researchers Create Hybrid Cheese with 25% Pea Protein”