While we try to keep things accurate, this content is part of an ongoing experiment and may not always be reliable.

Please double-check important details — we’re not responsible for how the information is used.

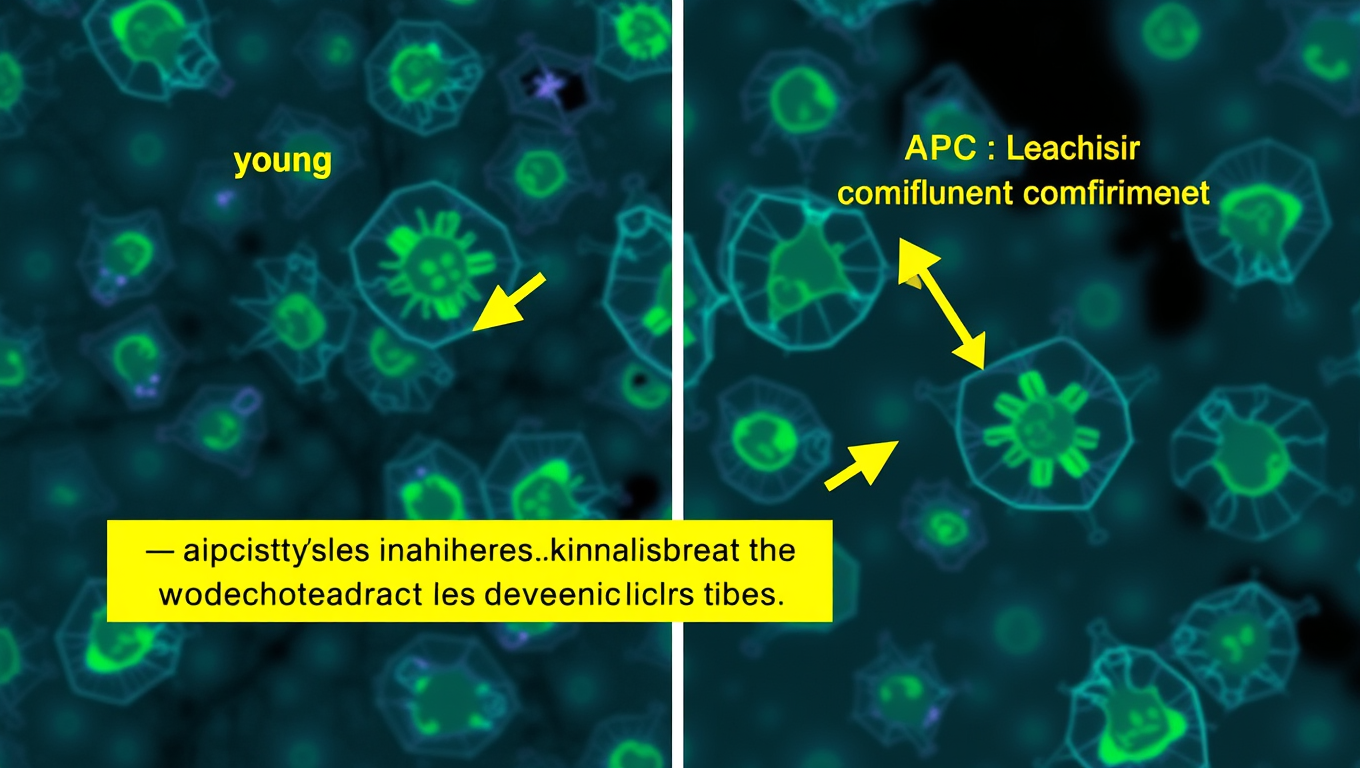

Diet and Weight Loss

Uncovering the Cellular Culprit Behind Age-Related Abdominal Fat: A New Target for Future Therapies

It’s no secret that our waistlines often expand in middle-age, but the problem isn’t strictly cosmetic. Belly fat accelerates aging and slows down metabolism, increasing our risk for developing diabetes, heart problems and other chronic diseases. Exactly how age transforms a six pack into a softer stomach, however, is murky. New research shows how aging shifts stem cells into overdrive to create more belly fat.

Birth Control

Scientists Uncover Groundbreaking Treatment for Resistant High Blood Pressure

A breakthrough pill, baxdrostat, has shown remarkable success in lowering dangerously high blood pressure in patients resistant to standard treatments. In a large international trial, it cut systolic pressure by nearly 10 mmHg, enough to significantly reduce risks of heart attack, stroke, and kidney disease. The drug works by blocking excess aldosterone, a hormone that drives uncontrolled hypertension.

Arthritis

The Alarming Impact of Routine X-Rays on Arthritis Patients’ Decisions

Knee osteoarthritis is a major cause of pain and disability, but routine X-rays often do more harm than good. New research shows that being shown an X-ray can increase anxiety, make people fear exercise, and lead them to believe surgery is the only option, even when less invasive treatments could help. By focusing on clinical diagnosis instead, patients may avoid unnecessary scans, reduce health costs, and make better choices about their care.

Dementia

Unlocking the Secrets of Women’s Alzheimer’s Risk: Omega-3 Deficiency Revealed

Researchers discovered that women with Alzheimer’s show a sharp loss of omega fatty acids, unlike men, pointing to sex-specific differences in the disease. The study suggests omega-rich diets could be key, but clinical trials are needed.

-

Detectors11 months ago

Detectors11 months agoA New Horizon for Vision: How Gold Nanoparticles May Restore People’s Sight

-

Earth & Climate12 months ago

Earth & Climate12 months agoRetiring Abroad Can Be Lonely Business

-

Cancer11 months ago

Cancer11 months agoRevolutionizing Quantum Communication: Direct Connections Between Multiple Processors

-

Albert Einstein12 months ago

Albert Einstein12 months agoHarnessing Water Waves: A Breakthrough in Controlling Floating Objects

-

Chemistry11 months ago

Chemistry11 months ago“Unveiling Hidden Patterns: A New Twist on Interference Phenomena”

-

Earth & Climate11 months ago

Earth & Climate11 months agoHousehold Electricity Three Times More Expensive Than Upcoming ‘Eco-Friendly’ Aviation E-Fuels, Study Reveals

-

Diseases and Conditions12 months ago

Diseases and Conditions12 months agoReducing Falls Among Elderly Women with Polypharmacy through Exercise Intervention

-

Agriculture and Food12 months ago

Agriculture and Food12 months ago“A Sustainable Solution: Researchers Create Hybrid Cheese with 25% Pea Protein”